|

|

| introduction | yap | pohnpei | chuuk | palau | marshalls | ||

|

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN POHNPEI

The Initial Struggle The Capuchin friars who landed at Pohnpei in March 1887 were not the first Catholic missionaries to work on the island. Fifty years before their arrival, in December 1837, a small schooner christened the Notre Dame de Paix brought Fr. Desiré Maigret and the body of his companion, Fr. Bachelot, who had died en route to Madolenihmw. With the help of two Mangarevans and two Hawaiians, Fr. Maigret spent six months trying fruitlessly to establish the faith on Pohnpei before leaving to resume work in Polynesia. The American Protestant missionaries who first came to Pohnpei in 1852 were much more successful. Half of the island population were church members and virtually all the rest heavily influenced by the Protestant religion by the time of the Spanish takeover. It was only when Spain gained full title to the Carolines after its controversy over the islands with Germany that Spanish authorities decided to establish a colonial government in the archipelago. The Capuchin Order was asked to furnish the missionaries to work in the islands, and the first friars departed from Spain in early April 1886. A few months later six Capuchins were sent to Yap to begin missionary work in the western Carolines. Meanwhile, the religious assigned to Pohnpei, the seat of Spanish rule in the eastern Carolines, remained in the Philippines while the government prepared its next expedition. Finally, in early February 1887, a party of government and missionary personnel departed from the Philippines and steamed eastward, stopping at Yap for some days along the way. On March 14, 1887, the ship anchored off the northern coast of Pohnpei at Mesenieng, the site of the new Spanish colony. The curious onlookers that lined the shore watched the Spanish governor, Isidro Posadillo, disembark, followed by the entire government entourage: the governor's secretary, two military officers, 50 soldiers, and 50 Filipino convicts. Also aboard the ship were six Capuchins assigned to work on Pohnpei: Fr. Saturnino de Artajona, Fr. Agustin de Ariñez, Fr. Luis de Valencia, Br. Miquel de Gorriti, Br. Gabriel de Abertesga, and Br. Benito de Aspa. The Capuchin Provincial, Fr. Joaquin Llevaneras, and his secretary had also come to help set up the mission. Within a couple of weeks, the Spanish colony–named Santiago de la Ascension–began to bristle with buildings including the church and Capuchin residence. The church dedicated to the Mother of the Divine Shepherd, was finished in time to hold the first public mass there on Palm Sunday, April 4. Two weeks later, on the same day on which the solemn proclamation of Spanish sovereignty was celebrated, the first Catholic baptism took place. The three-year old son of a Pohnpeian woman and Manuel Torres, a Filipino who had come to the island a few years before, was given the name of Isidro with all the solemnity that the missionaries could muster for the occasion. Later in that same week the missionaries celebrated another spiritual conquest when they received back into the church Narciso de los Santos, a Filipino who had been living on Pohnpei for 37 years and had spent the last several years as a lay teacher in the Protestant church. The Capuchins, under their superior Fr. Saturnino de Artajona, took up residence in their newly finished quarters and began laying plans for their difficult missionary work in a land that had recently been evangelized by American Congregationalists. Within a month of their arrival, Edward Doane, the sole American Protestant missionary on the island, was arrested when he ran afoul of Spanish authorities over a claim to land adjoining the colony. His arrest and deportation to Manila for trial were an indication of the new tensions emerging on the island in which the Catholic missionaries would soon become embroiled. At the end of April, the Nahnmwarki of Kitti paid a visit to the priests and asked them to establish a mission station in Alenieng. He had been at odds for some time with Henry Nanpei, a political rival and prominent church leader in Kitti, and hoped that the Catholics would act as a check on his growing power. Work was soon begun on the new mission station, although these efforts were soon abandoned as the first violence broke out. The new Spanish Governor had adopted a strong policy of forced labor in an attempt to obtain workers to complete the construction of the colony. Harsh and insulting treatment by the Spanish soon brought about a strike by Pohnpeian laborers. When the Spanish troops attempted to force the Pohnpeian laborers to return to work, some of the men from Sokehs and Nett opened fire and killed 20 of the troops. At the news of the slaughter, the Capuchins recommended that most of the Spanish be evacuated at once to a pontoon ship that lay in the harbor. Meanwhile, the priests carried on negotiations with the Pohnpeian warriors in their own residence for the next two days, as a small Spanish force guarded the colony. The negotiations came to nothing, however, and the remainder of the Spanish defenders withdrew to join the others on the pontoon boat. Governor Posadillo and several others were killed during the retreat. Fr. Agustin and Br. Benito, the last of the missionaries to withdraw, were almost abandoned when the Spanish boat pulled away from shore as the Pohnpeians opened fire; they were forced to drop their belongings and swim out to the boat. For the next several months they and the entire Spanish party took refuge on the old pontoon ship, Maria de Molina. Only with the arrival of three Spanish warships at the end of October was peace restored and Spanish control over the colony reestablished. The mission residence had been destroyed and all the Capuchins' possessions–medicine chest, carpentry tools, chinaware, library, and building materials–had been lost. The missionaries submitted a claim to the government for the 2,500 pesos worth of goods that had been ransacked and began the slow task of rebuilding. For a time they lived in a nipa hut barely large enough to hold the six of them; the roof was blown off in a strong wind a few nights after they occupied it. By the middle of January 1888 they started constructing a small chapel, six yards by four, out of whatever materials they could salvage from the ruins of the colony. The new governor, Don Luis Cadarso, was not especially sympathetic to the missionaries and would not provide materials for the construction. When they set out on one occasion to pick up some lumber from another part of the island, they met an armed group of Pohnpeians and were forced to turn back for fear of their lives. It was late in September before the ship arrived with building materials for the Capuchins' new residence. With the help of a couple of carpenters and a detachment of soldiers, the missionaries finally began work on the new residence, built of wood and roofed with zinc, which was finished on Christmas Day 1888. In January 1888, even as the Capuchins were resettling in the outskirts of the colony, they opened their first boys' school. These schools were normal appendages to all of the mission stations that the Capuchins established; in time they also added girls schools to their stations. The schools were initially very small, sometimes having no more than three or four students, who usually lived at the parish house with the Capuchins. Classes were usually held during the morning and included instruction in the Spanish language and catechism, with a little arithmetic and geography on the side. The young boys learned their mass prayers and religious hymns, and would help the lay brothers with work in the shop or garden during the afternoon. At the end of the school day students assembled to say the rosary in Pohnpeian and make an act of consecration to Our Lady. The first student enrolled in the school, a young boy given the name of Miguel, was baptized together with his mother at the end of his first year of instruction. His mother was sent off to Manila where she could continue her religious education at a school run by the Daughters of Charity. The conditions under which these missionaries worked were far from ideal. Between them and the Protestant pastors, both Pohnpeian and foreign, there was suspicion and mistrust, if not outright hostility. Their working relationship with the Spanish governor and his staff was not much better. The governor and some of his staff, influenced by accounts that had been published by the liberal press abroad, held the Capuchins indirectly responsible for the uprising of the previous year because of their aggressive stance towards the Protestant ministers and their people. For their own part, the missionaries had serious complaints about the government, especially regarding the lax morality that was so conspicuous around the colony. So many Pohnpeian women were visiting the colony to prostitute themselves, one priest wrote, "that one can not take a walk in any direction without falling over soldiers and kanaka girls in the most indecent postures." At least on their outrage at this wanton display of indecency Catholics and Protestants were in agreement. Both churches protested to the governor, who did very little to check the abuses. The missionaries opened their second mission station–the one that had been begun at Aleniang soon after their arrival–in July 1889. This project, which had been halted at the time of the first uprising, was afterwards delayed for several more months. The Capuchins themselves decided to postpone the opening of the station when they learned that the Nanmwarki of Kitti, who had initially requested the church, had dismissed his wife. Then the Spanish authorities stalled in providing the materials and the transportation for the project. But when Governor Cadarso began construction of a road between the colony and Kitti, the first leg of a road that he envisioned building around the island, he showed new enthusiasm for the mission and persuaded the missionaries to open the residence and church at once. On July 1, the Spanish ship Manila steamed into Mwudok Harbor off Wene with Capuchins, an official government party and some 80 troops to attend the solemn dedication. They were met by the Nanmwarki, dressed in European clothes, who showed the Capuchins to the modest residence he had prepared for them. The Capuchin residence was located near the Nanmwarki's house only 60 yards away from the Protestant church. On the following day a mass of dedication was celebrated in the tiny nipa church named for St. Felix of Cantalacio, and Fr. Agustin de Ariñez and Br. Benito de Aspa remained to staff the new church and school.

Spanish Capuchins outside the mission residence on Pohnpei During the following months, the two Capuchins assigned to Kitti set about replacing their small quarters and the hut that served as a chapel with more substantial buildings. By the end of October they and their Pohnpeian workmen had finished work on a comfortable wooden residence and church. The formal blessing of the new church that the missionaries had hoped to be a grand and solemn occasion was disappointing. The entire garrison of 40 soldiers from the Spanish fort nearby turned out for the occasion, firing cannon salvos at the end of the blessing, but very few others attended. Only a half dozen Pohnpeians, including the Nanmwarki and his wife, were in the church, and none of the Spanish officials bothered to come from the colony for the ceremony. Meanwhile, just a few yards away, the Protestant church was thronged with worshippers who had come from as far away as Madolenihmw to attend the three-hour service that Edward Doane ran. The meaning of the contrast was evident to the Catholic missionaries: they had the good will of the Nanmwarki of Kitti, but the Protestants had the support of the overwhelming majority of the people. The governor was soon pleading with the Capuchins to open a third mission station, this one in Ohwa, Madolenihmw. The priests had serious doubts about the wisdom of such a move, for they knew that since January 1890 rumors had been circulating that Madolenihmw was arming itself. Having met with delegations of chiefs from that part of Pohnpei, the Capuchins knew how bitterly opposed Madolenihmw leaders were to the establishment of a Spanish garrison there. Governor Cadarso, however, intended to continue the road-building project and determined to set up another fort at Ohwa, where he also hoped to have a church strategically located. The Capuchins yielded to his persistence despite the obvious dangers. In early June, Fr. Agustin and Br. Benito were assigned to the new mission in Ohwa, while Fr. Luis and Br. Miguel were sent from the colony to take their place at Aleniang. Fr. Agustin and his companion were feasted by the Nanmwarki at Temwen and sent on their way to Ohwa where they got along surprisingly well with the people. Despite their feelings about the project, Pohnpeians would come over to the temporary mission quarters in the evening to listen to Br. Benito play the accordion or to ask questions about religion. Even when the missionaries made it known that they would build their new church next door to the Protestant church, as they had done in Kitti, there was no public outrage on the part of the people. American church leaders protested to the governor, but they were ignored. Tension between Pohnpeians and the overworked Spanish garrison in Ohwa rapidly built up to the point of violence. In late June the people of Ohwa attacked the Spanish troops and killed over 30 of them. Fr. Agustin and Br. Benito, along with the few other survivors, were hidden in the dormitory of the Protestant school until they could be smuggled out to the Spanish ship that came to put down the rebellion. Over the course of the next several months the Spanish tried again and again to take reprisals and recapture Ohwa even as their casualties mounted. Finally, in late November, the Spanish successfully stormed the fort built by the defenders, but were soon forced to give up the position and withdraw to the colony. The Catholic buildings under construction had been destroyed in the fighting, and the Capuchins abandoned any plans to rebuild the mission there. This second outbreak of violence was very costly for the Spanish, who lost 118 men and spent nearly 200,000 pesos to put down the uprising. Spanish authorities, who were quick to blame the first uprising on the indiscretion of the Catholic missionaries, again looked for a scapegoat for this recent revolt. They found one in the Protestant missionaries, whom they accused of at least collaborating in the uprising if not actually engineering it. At the encouragement of Governor Cadarso, an American warship removed the remaining Protestant missionaries from Pohnpei, leaving Henry Nanpei the most influential Protestant leader on the island. Meanwhile, the Capuchins tended their two mission stations and strengthened their struggling schools. The small school in Aleniang grew in enrollment and enjoyed a sudden prosperity when the Nanmwarki of Kitti donated to the school some of the 500 pesos that he received yearly from the Spanish government. The new governor who replaced Cadarso in February 1891 visited the school twice, each time distributing to every one of the students the gift of a peso. In the colony the missionaries started the construction of a new school building in September. Until then nearly all the students had been boarders who lived and attended classes in the mission residence itself. As work began, the Capuchins had the usual problems in getting the government to assist them. At first the governor would not provide building materials, then would not supply troops for the labor. When soldiers were eventually detailed to assist in the work, they arrived late and were changed frequently, so Pohnpeians ended up doing most of the construction work themselves. At last, in February 1892, after five months' work and a 600 peso investment, the new school building was dedicated in a ceremony attended by all the highest chiefs on the island. The enrollment rose almost immediately to 30, the highest figure yet in the young mission. The early 1890s were frustrating years for the Capuchin missionaries. New governors followed one another in rapid succession–there were five between 1891 and 1894–but none proved capable of effectively dealing with the tension on the island. As one governor after the other despaired of ruling the island and settled for placating the chiefs, the Capuchins complained that the respect for the government was diminishing with each passing day, and with it the influence of the Catholic mission. When Governor Concha in 1894 let it be known that he planned to resume work on the road around the island, there was immediate ferment throughout the island, especially in Madolenihmw. Rumors spread of an impending attack on the colony. Soldiers who wandered too far away from their companions were routinely ambushed and killed. A Filipino convict who had lived for a time with the Capuchins while doing carpentry work on some of the mission buildings was found dead one day with an ugly gash in his throat. Fr. Agustin, the pastor of the Kitti church, spoke to the governor about the danger in attempting to carry out this course of action, but he was unable to change the governor's mind. The governor had also spread the word that he was inviting the American Protestant missionaries to return. This had a devastating effect on the Catholic schools; students withdrew in large numbers to await the return of the Protestant missionaries and the reopening of their schools. Only when authorities in Manila expressed their disapproval and censured his recklessness did the governor abandon these plans. Relations between the Capuchins and the government remained as bad as always throughout the remainder of Spanish rule. Several of the governors supported the work of the Protestant mission in the name of freedom of religion and a liberal ideology. Moreover, they tried to withhold government support for the Catholic church for the same reasons. This, of course, put them squarely in opposition to the Capuchin missionaries, who expected the same close collaboration between the church and the government that had existed throughout Spain's colonial history. An additional reason for the conflict was the unsparing attacks of the missionaries on the vices of the Spanish officials and troops. The colony had become a sewer of prostitution and wild drinking, the Capuchins maintained, and they forbade their converts to visit there even to sell produce. These continual denunciations, before governors in Pohnpei and in letters to Manila, did not improve the Capuchins' relationship with the government. In May 1893 the mission received new encouragement with the arrival of five new Capuchins to work on Pohnpei–Frs. Estanislao de Guernica and Bernardo de Sarria, and Brs. Carlos de Benisa, Julian de Vindaurreta, and Serafin del Real de Gandia. Three more Capuchins were added about the same time–Frs. Jose de Tirapu and Segismundo del Real de Gandia, and Br. Sebastian de Sanguesa. One of the mail ships for the same year brought copies of a dictionary of the Pohnpeian language compiled by Fr. Agustin, the most fluent of the missionaries in Pohnpeian. His book was the first published by the Catholics working on Pohnpei. In later years Fr. Bernardo produced a small dictionary of his own and Fr. Buenaventura published a devotional book under the title of Joulang Katek. Groundswell in the North The work of conversion had gone slowly during the early years of Capuchin activity on Pohnpei: by the end of 1893 there were fewer than 100 persons baptized into the church. Then, in 1894, rapid expansion suddenly began in the northern part of the island. The Nanmwarki of Sokehs visited the Capuchins to ask for a church and school in his territory; and on January 11, 1894, the new mission station, dedicated to St. Francis, was opened at Denipei. Fr Luis was put in charge of the new station, with Br. Sebastian assigned to help him. The following month one of the priests paid a visit to the Soulik to work out arrangements for the establishment of a new mission in Uh. The Capuchins were to pay the chief 135 pesos for the construction of the buildings and they would move in as soon as the work was completed. The project was far enough along to allow the Capuchins to open their school in March, although the church of St. Joseph in Awak was not dedicated until December 10, 1894. Fr. Luis and Br. Sebastian were transferred from Sokehs to care for the new mission station in Awak, while Fr. Bernardo and Br. Carlos took over Sokehs. The missionaries faced more difficulties in the southern part of the island. Fr. Agustin, one of the most versatile and best loved missionaries, had done all that he could to win the hearts of the people of Kitti during his years as pastor of Aleniang. Yet there remained some strong opposition to the Catholic church. He had hoped to begin a new mission station in Lohd, a kousapw of Madolenihmw not far from the Kitti border, but government policy forbade the opening of any mission without the approval of the Nanmwarki and other high chiefs of the territory. There was no chance of the Capuchins' obtaining such approval from Paul, the Nanmwarki of Madolenihmw, who still strongly mistrusted the Spanish and resisted all efforts to set up a Catholic mission in his area. Fr. Agustin had to be content with the one station at Aleniang to handle the entire southern part of the island. The overall mission picture was suddenly brighter than ever before. There were four mission stations in all, one in each of the kingdoms except Madolenihmw. The enrollments in the Catholic schools were higher than ever before, and each of them now had a separate class for girls. More than 70 students showed up for class at Awak on the day that the school opened, and daily attendance averaged about 50 afterwards. The three schools in the northern part of the island held a joint contest in reading and religion before the governor and his staff, who awarded prizes to the winners. Even the school in Kitti, which had been doing so badly that Fr. Agustin had packed up his mission supplies and was ready to give it up as lost, was receiving many new students. Soon a second school had to be opened in RohnKitti to accommodate all those who wanted to enroll. The new surge of interest in the Catholic religion had also made it necessary for Fr. Agustin to begin adult religious instruction classes each day. At the end of six months he recorded 21 baptisms, more than the total received into the church in Kitti in the previous five years. Six more Capuchins–four priests and two brothers–arrived in 1896 to further strengthen the mission. Fr. Saturnino, the superior of the mission since its founding, returned to Spain and Fr. Agustin was transferred to the mission center in the colony to replace him as superior. Fr. Bernardo was assigned to fill his former position as pastor of Aleniang, while Fr. Segismundo went to Sokehs and Fr. Jose took over Awak. Although two other Capuchins, Frs. Luis and Estanislao, also left Pohnpei at about this time, there still remained a good-sized staff of eight priests and eight brothers to care for the mission. Soon a string of baptisms of high-ranking chiefs occurred that strengthened the influence of the church beyond any of the missionaries' expectations. The Wasai of Sokehs was the first in March 1896. His baptism was a solemn and joyous occasion, celebrated in the main church in the colony amid colorful pennants, the ringing of bells and the discharge of muskets. After the Wasai and his wife received the sacraments and had their marriage blessed, they were brought into the mission residence for a reception complete with wine, sweets and cigars. The Soulik of Awak was baptized together with some of his people barely a month later, and the number of converts from Awak grew in subsequent months. A year later, in March 1897, the Nanmwarki of Kitti, who had supported the Catholic mission in his area from the beginning, was received into the church together with his whole family. The entire Spanish community on Pohnpei turned out in Aleniang for the occasion. The superior of the Gilbert and Marshall Island mission, along with the crew of his mission bark, also attended the long and elaborate ceremony. The governor, who served as godfather for the newly baptized chief and his wife, afterwards gave them a wardrobe of clothes and two large gold rings. A few months after this event the Nanmwarki of Uh and Lepen Nett asked to be received into the church. By the end of 1897 some of the highest chiefs of every kingdom of Pohnpei except Madolenihmw had become Catholic and the number of baptisms each year had grown to over a hundred.

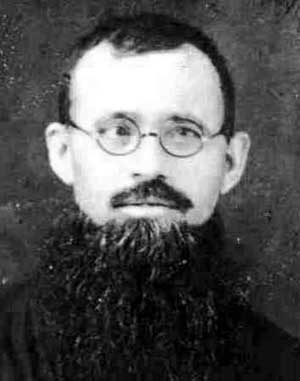

Br. Sebastian de Sanguesa, the last of the Spanish Capuchins to leave Pohnpei Within a short time, however, violence once again broke out on Pohnpei. One of the Protestant teachers from Mwahnd, angered by the governor's acquittal of the Soulik of Awak of charges of murdering a Protestant leader, began preaching a crusade to drive the Catholics out of Pohnpei. In March 1898 the forces from Mwahnd, supported by people from Madolenihmw and Uh, gathered their canoes off Awak to attack the mission there. At first the Awak people refused to answer their rifle fire, but finally they made a counterattack and after a three-hour battle drove the invaders off. The Spanish cruiser Quiros steamed into Awak the next day and arrested Nanpei, who was suspected of instigating the attack and supplying weapons to the invaders. The Spanish released him soon afterwards, however. A month later, after word had reached Pohnpei of the impending war between the US and Spain, the assault was resumed. This time a force of 900 men, rallied from Kitti as well as Uh and Madolenihmw, appeared offshore. The Awak defenders, supported by allies from Nett and Sokehs and aided by the Spanish warship, again routed their enemies. To guard against future attacks, Awak was fortified by a large wall and reinforced by a contingent of Spanish troops for the next several months. Although the worst of the fighting had ended, tension continued through the remainder of the year and into the next. The Madolenihmw people, encouraged by reports of American victories over Spain abroad, remained on the lookout for a way to renew the attack on Awak. American whaleships that appeared in January 1899 sold them guns and ammunition and provoked them all the more. The Catholic mission residence in Aleniang was plundered and burned to the ground, and the missionaries living there were forced to take refuge in the colony. When the Spanish troops who were stationed in Awak began molesting the women there, the Capuchins were forced to complain to the governor. This only further aggravated the differences between the missionaries and the government. Unfounded stories about some of the priests began circulating. Soon two of the priests, Fr. Bernardo and Fr. Segismundo, left the mission for good, and so Br. Julian was left to care for the Sokehs mission alone for the next three years. Fr. Agustin was taken sick in February 1899, and after treatment at the hands of one of the Spanish medical officers he experienced terrible stomach pains. He died two days later of what the Capuchins believed to be poisoning, possibly because of his strong denunciations of Spanish abuses. When the Spanish ship España arrived at Pohnpei in May 1899, it was flying the American colors and brought an interim governor, the last of a line of 12 Spanish administrators. With the sale of the Carolines to Germany the following month, the Spanish officials and troops could settle back to await their release from Pohnpei. This was not the case with the Spanish missionaries, however. They would continue to bear the responsibility of caring for Pohnpei during the early years of German rule until they were eventually replaced by German Capuchins from 1904 on. With Fr. Jose Tirapu as mission superior, the diminished group of Capuchins–then three priests and five brothers–did what they could to provide pastoral care for the island. Despite their reduced numbers, the Capuchins expanded their mission network. In 1899 they opened a new station at Nanpohnsapw, Nett, which was entrusted to the care of Fr. Juan and Br. Ricardo. Soon after this, Fr. Jose and the new German governor visited Aleniang to inspect the ruins of the former mission station, where they found the site overgrown and very little left that could be salvaged. The governor, out of sympathy for the missionaries, wanted to hold the vandals responsible for paying damages, but Fr. Jose felt that this might inflame old passions once again. Instead, he chose a new site at Roi, the center of the small Catholic community in Kitti, and sent Brs. Benito and Carlos to begin work on the new church, residence and school. Like the former station at Aleniang, this new one was dedicated to St. Felix of Cantalacio. With only three priests for the entire island, some of the mission stations were occupied only by brothers for the greater part of the time. Brs. Benito and Carlos were assigned to care for Roi until Fr. Buenaventura was later transferred there. Br. Julian lived alone in Awak administering the station and running the school, and he was afterwards assigned to Sokehs where he assumed the same responsibilities. The priests were stationed in the colony and Nett and visited other churches on weekends to say mass and attend to other pastoral needs. Under this kind of patchwork arrangement it was inevitable that the school enrollment and mass attendance would decline. Many of those who had been received into the church during the groundswell of enthusiasm in the mid-1890s fell away, some of them returning to Protestantism. The Spanish missionaries no longer enjoyed the active support of the government for their work, even if this support had not always been willingly rendered during Spanish times. The annual subsidy of 14,000 pesos that the Pohnpei mission received from the Spanish government had been discontinued, and the mission's financial situation was critical. Yet, despite the lack of funds and manpower, the Spanish Capuchins could count over 800 Catholics among their flock by the time that German Capuchins took over the mission in 1904. Considering the troubled times in which they worked, this was a remarkable achievement. Beginning Anew The new German government in the Carolines praised the conduct of the Spanish missionaries and expressed a willingness to have them continue their work in the islands. Nonetheless, the social and political realities on Pohnpei had clearly changed. Schools were encouraged to teach the German language and a government subsidy was provided to assist them in this. German was to be the lingua franca in the area and missionaries who did not speak the language would be at a serious disadvantage. Recognizing this situation, the Capuchin Order sent out its first two German missionaries in 1903. One of them was sent to Yap and the other, Fr. Victorin Louis, was assigned to Pohnpei to begin teaching German in the mission school in the colony. A year later, in November 1904, the mission of the Eastern Carolines was formally entrusted to the German Capuchins of the Rhine-Westphalian Province. Within a month the first contingent of German missionaries, seven in all, arrived at Pohnpei. Fr. Venantius Duffner, the Capuchin superior on Pohnpei and the apostolic administrator of the entire Caroline mission, took up residence in Kolonia. With him lived Fr. Victorin and four brothers: Othmar Gesang, Melchior Majewsky, Kolonat Metzen, and Koloman Wiegand. Fr. Fidelis Dieterle went to Kitti to take possession of the mission station that had been transferred to Roi just a few years before. The transition from Spanish to German missionaries was swift. Within the next few months four of the six remaining Spanish Capuchins left the island for Europe. Only two brothers stayed on to help staff the mission stations until more personnel arrived from Germany. Br. Sebastian worked for a time with Fr. Fidelis in Kitti, while Br. Julian continued to maintain the station at Awak, which still had no priest. The new missionaries lost no time in settling down to work. One of the first things the new superior did was to purchase seven hectares of land in Kolonia, the present site of the mission, on which he planned to expand the church quarters. Meanwhile, the Germans began teaching classes in the four mission schools, with their total enrollment of 125, that were then in operation around the island. They soon also initiated requests to have German teaching sisters come to the islands to instruct Pohnpeian girls. The normal round of mission activities came to an abrupt halt on April 20, 1905, when a fierce typhoon devastated the island. The typhoon brought death to a dozen Pohnpeians and injury to another 200 or 300, destroyed most of the housing on the island, and left the people seriously short of food. It also leveled almost all of the mission buildings in different parts of the island; only the churches in Sokehs and Kitti were spared, and even these were badly damaged.  German Capuchins on Pohnpei in 1908 The energies of the new missionaries were soon directed towards a massive rebuilding effort. Recruiting 50 Pohnpeian men as laborers, the Capuchins installed them and their families in two large dormitories that had been hastily erected and provided canned food and rice (180 bags of it) for everyone for the next several months. Building materials were expensive and mission funds were limited, but the reconstruction began almost immediately. Within a few months the missionaries and their Pohnpeian workers had replaced the church, school and residence in Kolonia with what were intended to be temporary buildings. More permanent structures would be started in time as funds allowed. Br. Koloman made other improvements in the Kolonia mission as well; he cut a channel and built a boathouse on the new property, cultivated a garden, and cut paths leading to the prospective site of the new church and residence. All the while, he and the other German brothers cooked meals for the laborers and their families, kept a sharp lookout for fish and whatever other little local food might be offered for sale, and served as dentist and physician for all. Meanwhile, reconstruction was also going on at the other mission stations. Fr. Fidelis put in a boathouse and dock of his own in Kitti after repairing the buildings that had been damaged in the storm. Br. Othmar was sent to Awak to supervise the rebuilding of the residence and the small church which also served as a school. All day long Br. Othmar would work with his Pohnpeian assistants under the watchful eye of the Soulik of Awak, and at the conclusion of the day's work, the Soulik would invariably hand Br. Othmar a cup of sakau with an approving nod. Only in Sokehs was no attempt made to rebuild or repair typhoon damage. As it was, the mission's resources were taxed to the limit by the rebuilding program. The Capuchins had spent nearly 20,000 marks by year's end and Fr. Venantius was obliged to send urgent requests to Europe for emergency funds.

Br. Othmar at work on the new church There was at least one positive effect of the typhoon. The people of Takaiu, perhaps inspired by the efforts made by nearby Awak in rebuilding their church, decided that they too wanted a church on their island. In the months following the storm they built a chapel and 50 catechumens presented themselves for instruction for baptism. Their church was dedicated in honor of St. Fidelis in September 1905 and the island became a sub-station thereafter. Less than a year later, another mission station was opened on the island of Parem in Nett. With the arrival of three more Capuchins–Fr. Crescenz Huster and Br. Eustach Kessler in 1905 and Fr. Gebhard Rüdell in 1906–the German missionaries at last had adequate manpower to assign a priest to each of the four main mission stations. Fr. Gebhard took over the Sokehs church, and Fr. Victorin was sent to Awak together with Br. Eustach, who replaced Br. Julian, the last of the Spanish missionaries to leave Pohnpei. Fr. Crescenz was soon made pastor of the Kolonia church, while Fr. Fidelis continued to care for the Kitti church. A Capuchin brother was assigned to each of these stations to assist the priest in charge. Fr. Venantius, who had worked in Kolonia while exercising his authority as prefect of the entire Caroline mission, prepared to move the seat of the mission to Yap. This he finally did in 1907 because the newly completed cable station there allowed him to communicate easily with the outside world. Pohnpei was also strengthened by the arrival of the first three Franciscan nuns in January 1907. The three–Sr. Buenaventura, Sr. Bernardina and Sr. Katharina–were met at the dock and escorted to the mission property in procession. There they found the buildings decked with bunting and festooned with flowers and the grounds thronged with Pohnpeians who had come to greet them. After the usual religious ceremony ending in the singing of the Te Deum, they were installed in the new convent built for them, a building complete with running water. A few days afterwards, the sisters were in the classroom in Kolonia instructing young Pohnpeian girls in German, arithmetic, and the catechism, not to mention choral singing, dictation and what could be called home economics. They ran a dormitory for girls similar to the one for boys run by the Capuchins in Kolonia, and also taught German language classes to adults in the evening. Their impetus was felt in the schools at the other mission stations as well, and soon there were separate schools for girls and boys attached to each mission residence. Within two years of their arrival, there were more than 250 students altogether over half of them girls. A few of the teachers in these schools were Pohnpeians. Evangelization proceeded well on Pohnpei during these years. New converts were being made in Kitti through the work of Fr. Fidelis, while the missionaries continued to exercise strong influence over the northern part of the island. Palikir was the only really pagan stronghold in the north, but even that began to change by the end of the decade. The missionaries were averaging about a hundred conversions a year during this period, and the Catholic population had grown to about 1,200 by 1909. Another savage typhoon, that which devastated the Mortlocks in March 1907 claiming over 200 lives and stripping the islands of all produce, had provided the missionaries with new pastoral opportunities. In the months following the typhoon several hundred Mortlockese had been brought to Pohnpei to find livelihood and a new home, and the Capuchins began to make conversions among these people as well.  German Sister working with school girls

The German missionaries wrote back to Europe of the impressive faith of many of their converts. One woman from Awak who had taken the name of Conception at baptism brought her six young nephews to church for mass every morning without fail. In the evening she and her brood would return over the rough and muddy path to attend rosary. From time to time there were especially moving demonstrations of the strength that the Catholic faith had attained on Pohnpei. One such occasion was the feast of Corpus Christi in 1910 celebrated with a solemn mass and procession that drew between 800 and 1,000 Catholics from all parts of the island. Since the large stone church that was being built in Kolonia was not yet finished, the mass had to be held outdoors to accommodate the huge numbers. Behind the young men and women under the large banners of St. Aloysius walked small girls dressed in white strewing flowers along the road, while four of the highest chiefs on the island carried the canopy covering the Blessed Sacrament. As the procession moved from one temporary altar to another, the choir sang Latin and Pohnpeian hymns and the people recited the rosary. To feed the devotion of their people, the German missionaries published several books and pamphlets in Pohnpeian. An illustrated bible history and a catechism, both translated by Fr. Crescenz, appeared about the same time that a book of prayers and a hymnal were published. A geography book in German was printed especially for the students in the mission schools on Pohnpei. After 1911 the Capuchins also began publication of a periodical that was issued under the title Uju nan Matau (Star of the Sea). The addition of another priest and brother (Fr. Ignatius Ruppert and Br. Gereon Gerster) in 1908 and another sister to the teaching staff the following year provided the necessary personnel to carry on these new activities. The Uprising and Its Aftermath Even as mission work advanced, however, there was growing unrest on Pohnpei. When Georg Fritz assumed the position of district officer in 1908, he had introduced laws designed to reduce the tribute paid to chiefs and had imposed forced labor on all Pohnpeians as a government tax. The discontent grew more serious when his successor, Gustav Boeder, announced plans to rebuild the long-neglected road to Kitti and summoned the Sokehs people to begin work on it since they had not paid their labor tax for the previous year. Finally, in October 1910, matters came to a head when one of the German supervisors beat a Pohnpeian and the laborers went on strike. As feelings grew more heated and the Pohnpeian workers threatened the lives of the Germans, the latter fled to the mission residence in Sokehs and remained with Fr. Gebhard. When Boeder and his secretary came from Kolonia to settle the problem, they were killed and their bodies disfigured. Alarmed at what had happened, the Germans who had taken refuge in the mission slipped out of the mission residence and were themselves killed while trying to reach the dock. The German community retreated into the colony, fortified it as best they could, and called on people from the other parts of Pohnpei to come to their defense. Meanwhile, the Sokehs people with their allies took up positions close to the walled enclosure and opened fire on the defenders. The Catholic mission, which lay just outside the fortified colony, was exposed to the gunfire even though it was never directly attacked by the Sokehs people. At the first sound of gunshots, the sisters hustled the boarding school girls into the church, while the Capuchins took the boys into the cellar. The siege continued for the next 40 days. Normal mission activities were carried on during most of this time, but always in a climate of apprehension and uncertainty. Pohnpeians attended rosary in the early evening with their beads in one hand and a knife in the other, and the brothers worked at their chores on the mission grounds with a rifle at their side. Even after the arrival in early December of the first German ships with supplies and a detachment of Melanesian troops, the tension continued. Only in early January 1911 were enough reinforcements and guns landed to allow the Germans to begin their counteroffensive against the Sokehs rebels. By the end of February the Germans had forced the surrender of the Sokehs warriors, pursued the handful of fugitives to the interior of the island, and executed the ringleaders of the uprising. Not long afterwards, over four hundred Sokehs people were rounded up by the German government and sent off to Palau in exile. Following the uprising there were the usual attempts to lay the blame on one religious faction or another. Fritz wrote a pamphlet accusing the Capuchins of fanning hostiling there were the usual attempts to lay the blame on one religious faction or another. Fritz wrote a pamphlet accusing the Capuchins of fanning hostilities towards the Protestants, and a German woman who visited the island for a day or two published a wild attack on the Catholic missionaries and their work. Nearly everyone else, however, agreed that the reforms introduced by Fritz and furthered by Boeder, along with the insulting behavior of the German road foremen, were the major causes for the rebellion. Henry Nanpei's role in the whole affair is uncertain, but it was undoubtedly a significant one, for his personal influence had only increased with the years. Both the Catholic mission and the Protestant mission (since 1907 under the control of the German Liebenzell Society, with Germans replacing the American missionaries) distinguished themselves for their attempts to mediate the difficulties and restore peace to the island. The uprising and its aftermath brought significant changes to the mission. Since Sokehs was virtually deserted after the exile of several hundred of its people, the mission station there was closed and Fr. Gebhard was sent to begin a Catholic mission in the Chuuk area. A considerable number of the Mortlockese who had made their home on Pohnpei after the typhoon of 1907 had become Catholics, and for some time they had been asking for a missionary to be sent to their own islands. In April 1911, Fr. Gebhard and Br. Eustach left Pohnpei to found a new mission on Lukunoch. In succeeding years Pohnpei served as a training ground and staging area for the new mission field in the west, especially after the expansion to Chuuk itself in 1912. Fr. Severin Oppermann, who had spent two years working on Pohnpei, replaced Fr. Gebhard in the Mortlocks in 1912, and in the same year Fr. Ignatius was assigned to Chuuk to become the superior of the new mission there. Within a year or two, Br. Melchior, one of the first German Capuchins on Pohnpei, also went to Chuuk, where he died in a building accident a year or two later. Meanwhile, Fr. Placidus Müller, a missionary in Palau who had begun working with the Sokehs exiles in Aimeliik, was transferred to Pohnpei. After many lean years, the Capuchins were beginning to make real headway in the southern part of the island. In Kitti, where Fr. Crescenz had taken over as pastor in 1909, there were soon more Catholics than in the Kolonia parish. The large number of converts, especially in Enipein, had raised the Catholic population to over 500 even as it brought about a shift in the center of church activities. Since the old mission buildings in Roi were dilapidated and in need of replacement, the Capuchins decided to move the site of the church to Wene, a place that lay midway between the two Catholic strongholds of Enipein and Roi. The missionaries purchased three hectares of land in Wene and moved the church and residence there in 1911. Unfortunately, the pastor became the target of rumors of a scandal, later proved to be false at a libel hearing conducted by the German government. Although his name was cleared, he was withdrawn from Kitti and sent to Awak. The Capuchins even opened a station in Madolenihmw, an area that had always had the reputation of being militantly anti-Catholic. When two of the chiefs in this section had converted to Catholicism some years before, they had been stripped of their titles and land. One of them, the Dauk of Madolenihmw, was banished for this and other alleged acts of insubordination. Their families had been converted to Catholicism, however, and the number of Catholics in the area soon approached a hundred. It was time, the Capuchins felt, that they took steps to provide these people with pastoral care and perhaps begin to proselytize others in the area. As it was, the Capuchins had for some time wanted to obtain a copra plantation to provide a regular source of income to help defray growing mission expenses. They had bought 20 hectares in Awak for this purpose, but they needed a larger estate than this. In 1910 at a public auction they purchased a 100-hectare plot of land that had once been owned by the German overseer Hollborn, one of the first to be killed in the uprising. The family of Hollborn's Pohnpeian wife had given him the land, but German land law required that the land be auctioned at his death if there were no sons to inherit it. This land, situated in Tamworoi, was not only ideal for the plantation that the missionaries hoped to establish, but it was a foot in the door in a district in which Catholics had never yet been able to set up a station. At first, the chiefs of Madolenihmw refused to allow the Catholics to make use of their landholding there, but they eventually gave way and in January 1913 the first church and school were opened there.  The German-built cathedral on Pohnpei The mission headquarters in Kolonia was taking on a new face during this same period. A year or two before the Sokehs rebellion, three Capuchin brothers had begun work on a new stone church to replace the temporary wooden building that had been put up after the typhoon in 1905. On the mission grounds they had set up a sawmill that employed waterpower from a stream; there were also brickwork and a kiln in which they could make the cement they used on the new church. This small industrial complex was the pride of the colony, and visitors were almost always brought over to see these amazing achievements. The church that was then being built was even more impressive, however. With its tall belltower and the graceful lines of its arches, it resembled a small-scale European cathedral more than a Pacific island church. Work on the church was nearing completion when the announcement was made in 1911 that the Caroline Islands, now juridically rejoined with the Marianas, would be elevated to the stature of a vicariate and would soon have its first bishop. The following year Salvator Walleser, a Capuchin who had spent six years in Palau, was consecrated bishop of the vicariate. He arrived at Pohnpei, which was to be his episcopal seat, late in the same year, and the church, finished a few months later, immediately became his cathedral. With the new bishop installed, Fr. Venantius was now free to leave Yap, where he had been directing church affairs, and return to Pohnpei to resume his old position as pastor of Kolonia.

Interior of the Pohnpei cathedral during mass The Catholic mission on Pohnpei had never flourished more brightly than on the eve of the outbreak of World War I. There were now 1,500 Catholics comprising nearly one-third of the population of the island, and more than 350 students attended the six mission schools. It was all the more of a blow, therefore, when on an October day in 1914 a Japanese warship steamed into the harbor, disgorged hundreds of troops, and announced the seizure of the island. After they had disarmed the handful of German officials and troops, the Japanese marines stormed the mission with fixed bayonets and machine guns trained on the buildings. After a thorough search of the premises, an officer apologized for the inconvenience and explained that his men were looking for weapons. Thereafter the missionaries were left to their work, at least for a time. For the next year the mission found that any communication with other parts of the world was impossible. Without the foreign subsidies on which the mission depended, funds were running very low, and so Bishop Walleser left by Japanese steamer for the U.S. to solicit financial help for the struggling mission. Although successful in getting money to the mission, he himself was refused permission by Japanese authorities to return to the islands. The mission received other severe setbacks as well. Fr. Crescenz, one of the most beloved pastors, died on Pohnpei in 1915, a year after Br. Othmar had passed away. The Franciscan teaching sisters were expelled by the Japanese in 1915 and all the mission schools were closed by order of the new government. The remaining Capuchins worked as best they could during the next few years under increasingly heavy restrictions. They were permitted to say mass and give the sacraments, but could do little more than that. Community meetings, even for religious purposes, were forbidden and the missionaries' travel was curtailed more with each passing month. Finally, in the summer of 1919, the three priests and five brothers who persevered in their work on Pohnpei were summoned by the Japanese governor and told to pack their personal effects. Within a few hours they were on a vessel bound for Yokohama taking their last look at the island where they had worked so long and hard. The German missionary epoch on Pohnpei was over, but the foundations for Catholicism they had built would survive. Building on Former Foundations Within two years the young church on Pohnpei had foreign missionaries once again. As soon as the Japanese won formal title to the islands in 1920, an emissary was sent to the Vatican to negotiate for the return of missionaries from a neutral country. Pope Benedict XV called on the Spanish Jesuits to take over the mission in which Capuchins had worked so well for over 30 years to plant the faith, and preparations were immediately made to send the first expedition of new missionaries to Micronesia. In April 1921 five Jesuits arrived in Pohnpei: Frs. Luis Herrera and Pedro Castro, and Brs. Victoriano Tudanca, Antonio Garcia, and Paulino Cobo.  The first Jesuit missionary expedition to Micronesia: Spain, 1920 Fr. Herrera and Br. Tudanca reopened the parish in Kolonia, where the amazing complex of buildings constructed by the German Capuchins stood ready to use. Fr. Castro and Br. Cobo went to Kitti, where a few years before a Catholic community only slightly smaller than the one in Kolonia had flourished. The years of absence had taken their toll, especially of the rickety house and church in Kitti, and the new missionaries found that some of their flock had drifted away. Yet, they could only marvel at how well the foundation for the church on Pohnpei had been laid by their predecessors. When the Angelus bell rang, people stopped, reverently made the sign of the cross and said their prayers. At the sight of the priest carrying the Blessed Sacrament through the village to a sick person, Catholics dropped to their knees. Masses on First Fridays were crowded with people who had learned this devotion from the Capuchins, and the priests soon received requests to reorganize the Apostleship of Prayer in their parishes. The Jesuits found the Catholic communities surprisingly well intact. The tiny group of Catholics on Parem, who had been meeting for the rosary on their own during the past few years, immediately asked Fr. Herrera to begin saying mass monthly at their small chapel. At Nanpihl the sister of the Nanmwarki of Nett, Carmen, had taken charge of the small community; she prepared the children for first communion, taught them their prayers and checked to make sure they were wearing shirts for mass. She also directed the pastor to the infirm and elderly, and had even begun rallying her people to build a larger chapel. Fr. Herrera found a valuable assistant in Luis Kio, son of the English beachcomber Joseph Kehoe, who had taken over major responsibility for the church during the absence of priests, baptizing and giving religious instruction. Luis lived with his family at the edge of the mission land in Kolonia. While his wife acted as sacristan and did the laundry for the missionaries, Luis accompanied Fr. Herrera on all his sick calls and visits to the different parts of his parish, soon becoming the foremost catechist in the northern part of the island. The Jesuits soon began regular catechism classes for the children. Gathering them each day, the priests–or in their absence, the brothers–instructed them in the mysteries of their faith, often using large posters for this purpose. It was an awkward arrangement, not only because it had to be done through a translator but because the children, who sometimes lived great distances from the mission, would straggle in late throughout the instruction. Schools like those run by the Capuchins would have been preferable, but the Jesuits did not yet have the personnel and the knowledge of the language to open such schools. To provide an inducement for the youngsters to come to Catechism class, the missionaries began raffling off objects that they received from Spain: balls, toy flutes, rosaries, bits of colored cloth, second-hand clothes, or anything else that children (or their parents) might find attractive. These raffles became a regular feature of early Jesuit catechesis and continued for years. Working largely through the children, the missionaries waged a vigorous campaign to win converts from among the numerous Protestants on the island. One nine-year old Protestant boy from Kitti who had been attending catechism lessons told his parents, when they refused him permission to become a Catholic, that he would not return home until they changed their mind. The parents soon consented to his baptism and in time became Catholics themselves. Another young boy from Sokehs also left home until his father agreed to let him become a Catholic. The result was much the same: the child was instructed by the catechist Luis, received into the church, and soon afterward followed by his entire family. But the outcome of these incidents was not always as happy for the Catholic missionaries. Protestant church leaders reacted strongly to the priests' aggressive campaign for converts, particularly through what they regarded as the stealthy conversion of their children, and feelings grew heated on occasion. The Nahnken of Uh was distraught when he learned that his daughter had become a Catholic, but upon hearing that his son had been secretly baptized despite his own adamant opposition he was furious. When he was told that the priest had somehow persuaded the Nanmwarki of Uh to become a Catholic, his fury could not be contained. The Nahnken succeeded in postponing the baptism each time it was scheduled until the priest forced the issue and called on the two chiefs to demand an explanation. The Nahnken, pushed to the limits of his patience, raged at the priest for his impudence and threatened to take up arms against the Nanmwarki if he ever became a Catholic. The Nanmwarki admitted that he could not become a Catholic under those conditions, and the priest went away disappointed. In January 1922 three more Jesuits arrived, including Br. Juan Ariceta and Fr. Ramon Lasquibar, both of whom eventually served for many years on Pohnpei, while one of the brothers who had come the previous year was transferred elsewhere. With this the missionary force on the island reached full strength and a third parish was reopened in Awak. For the next 20 years there would be three parishes, with a priest and at least one brother living in each. Fr. Pedro Castro, one of the first arrivals, was transferred to Awak together with Br. Cobo because leg injuries had made it difficult for him to do the walking required in his vast Kitti parish. Fr. Lasquibar, who was already 50 years old and not very spry himself, was assigned to the Kitti parish, where he remained for the next several years. Fr. Herrera, with the help of Br. Juan Ariceta and Br. Tudanca, continued as pastor of Kolonia for two more years. With the parishes now staffed and functioning, the missionaries turned their eyes to the outer islands, which had been left virtually untouched by the Capuchins. In August 1922 Fr. Herrera and his inseparable catechist Luis took a small copra steamer to Ngatik, bringing with them a handful of Ngatikese who had become Catholics on Pohnpei. Also on board the small steamer were a band of Pohnpeian Protestant pastors who had decided to go to bolster the Ngatikese against the Catholics as soon as they heard of his proposed visit. While Fr. Herrera dispersed his Catholics through the island to preach to any who would listen and to show people the catechetical posters, the Protestant leaders held continual meetings with the people to stiffen their resistance to the new religion. As usual, it was the children who were among the first to be baptized, with a number of adults following in their wake. Medals, scapulars, holy pictures and other Catholic emblems were freely distributed, while the cadre of catechists carried on their instructions with those who showed the slightest interest in Catholicism. By the end of his twelve-day stay on the island, the priest had received about 60 people into the church and plans were being made for building a church on his next visit.

A village church and residence on Pohnpei Ngatik thereafter became a regular destination for the pastor of Kolonia and yearly visits were made there. Before long there was a flourishing Catholic community of over a hundred. When the priests later made visits to Kapingamarangi to try to make inroads on that island, they found the results disappointing by contrast. A mere dozen or so people were converted on the first visit, although the number of Catholics grew in time to about 60. The priests subsequently did what they could to minister to the Catholics on that island, but decided that future efforts to convert Kapingamarangi and Nukuoro would probably prove futile. Ngatik, meanwhile remained the only outer island in the Pohnpei area that had any sizable Catholic presence. Meanwhile, Fr. Castro was finding his new parish in Awak more demanding than he had anticipated. Attached to his parish was the sub-station of Tamworoi with its fervent community of about 150 Catholics and the large copra plantation to be cared for. The Catholic population, which had met regularly for rosary and prayers all the while, had fared much better than the plantation, now badly neglected and in need of considerable work. Pigs roamed at will and their owners pleaded that they could do nothing to restrain them. The pastor was forced to evict the families who had built homes on the property and hire a group of workers to clean the land and collect the copra each month. While he divided his time between Awak and Tamworoi, Br. Cobo was at work supervising the construction of thatch buildings that could serve as shelters for the parishioners and classrooms for the catechetical lessons. There were minor setbacks for the missionaries, as when their canoe overturned and a shipment of several boxes of supplies recently arrived from Spain were lost, but the parish was clearly fervent and had rich potential. On the pastor's biweekly visits to Takaiu for mass, the entire small community there turned out and received communion. Mass attendance at Awak itself was impressive and the parish congregations were very active. Although the Nanmwarki of Uh remained a Protestant, there was a steady stream of converts, among them some influential kousapw chiefs. In addition, a 13-year old boy from Awak left Pohnpei in June 1923 to join four young men from other parts of the mission at the minor seminary in Manila. Hardly two years after the arrival of the Jesuits, Paulino Cantero was off to begin preparation for the Jesuit priesthood. The fortunes of the Awak parish suddenly took a turn for the worse when the church burned to the ground in the summer of 1923; nothing was saved except the Blessed Sacrament. Thereafter mass had to be held in one of the rooms of the Jesuit residence with the congregation standing outside exposed to the sun or rain. As soon as funds could be found, Br. Gojenola, that master craftsman and jack-of-all-trades, was sent to Awak to begin construction of a new church. Meanwhile, however, there were several changes in mission personnel that necessitated a reshuffling of the pastors several times in the next few years. With the departure of Fr. Luis Herrera, the pastor of Kolonia for the previous three years, Fr. Castro was transferred from Awak back to Kitti. The two priests who succeeded him in Awak, Fr. Ramon Suarez and Fr. Jose Pajaro, spent only a short time in Pohnpei between assignments to the Marshalls, and the parish was left without a pastor for over a year. In July 1926 a new arrival to the mission, Fr. Higinio Berganza, was temporarily assigned to the parish just as work on the new church was being completed. The church, situated above a stream, was a magnificent structure for its day with its pseudo-gothic design and its ornate wooden altar rising in three turreted niches, each containing the statue of a saint. The church was the genuine product of community labor; while many of the men in the parish sawed lumber and hammered nails, some of the more skilled local artisans were responsible for doing the doors, the baptismal font and other finer detail.  Awak church and school Finally, on December 8, 1926, the new church was solemnly consecrated. Santiago Lopez de Rego, who was made bishop of the vicariate two years earlier, made his first episcopal visit to Pohnpei in time to bless the church. Arriving by boat from Tamworoi, the next to last stop on his tour of the mission stations around the island, Bishop Rego was led under a pallium made from a tablecloth (for lack of anything else) through a triumphal arch decorated with bunting and garlands. The solemn mass of dedication, attended by hundreds of people and nearly all the Jesuits on the island, was followed by confirmations and baptisms. The feasting continued for two days afterwards. The only thing that was missing, Br. Cobo wrote, was a cast iron bell, which in due course of time arrived by ship and was carefully transported to Awak, where its installation was the occasion for a new celebration. Within a few months of the completion of the Awak church, Fr. Berganza was reassigned to the Kolonia Parish where he served as a pastor for the next nine years. There he faced a problem that had vexed the Jesuits from the very beginning. What could be done to provide the solid formation that Pohnpeians needed if the faith was to take deeper root in their hearts, particularly in view of the weight of the cultural influences that seemed to be opposed to Catholic teachings? Ordinarily the Jesuits would have opened schools, as the Capuchins had done, in order to provide more intensive training for at least some of the children in the hope that they would become dedicated parents, if not catechists, and serve as models of good Christian living. Under the Japanese, however, schools were a practical impossibility. The government jealously reserved to itself the right to educate the young, and all instruction had to be done in the Japanese language in any case. Classes in the public school began at eight each morning and ended at one in the afternoon, after which students started the long walk home on empty stomachs. Under such circumstances it was asking too much of the tired and hungry children to gather them for catechism class during the afternoon, as the missionaries found out when they experimented with this for a while. The only solution was to establish dormitories for as many students as space and funds would permit, provide meals for these boarders, and set up a supplementary course of instruction that might furnish them with some useful skills and nourish a deep commitment to their faith. Br. Burzaco had already set up a small dormitory for boys in two empty rooms in the rectory, but quarters were cramped and no more than a dozen could be accommodated. There was still no such facility for girls, although they too attended the public school in almost equal numbers. The Jesuits had long dreamed of having sisters working on the island to open a girls' dormitory. Hence the announcement that the Mercedarian Missionaries of Berriz were willing to send sisters to Pohnpei for this purpose was greeted with great enthusiasm. The large casa de piedra, or "house of stone," as it was called–the building that once served as the German sisters' convent–was prepared for their use as a residence and girls dormitory. In November 1928, the four Mercedarian sisters assigned to Pohnpei arrived with Mother Margarita Maturana, the Superior General of the Order. Their reception was similar to the one Pohnpeian Catholics gave to the German Franciscan sisters 20 years before: there was the procession from the wharf, the sung Te Deum in church, the speeches of welcome and the inevitable feasting. The reception was well deserved, for two of the four sisters, Sr. Concepcion and Sr. Belen, would serve in Pohnpei for over 30 years, and the new religious order would continue its work with distinction up to the very present.

Mercedarian Sisters with girls on a picnic The new boarding school opened almost immediately with 20 girls. The sisters began instruction in academic subjects as well as what we would today called home economics: cooking, washing, ironing, making bread and even stitching shoes. The girls also cared for the chickens and pigs, cleared the land and farmed, and in moments of leisure made attempts at playing the piano. They also learned their catechism, attended rosary and mass daily, and imbibed deeply of the piety and discipline of their spiritual mothers. When the renovations on the stone house were finally completed, the number of boarders increased to 50 or 60. For others in the parish who did not receive such intense formation, there were a number of active congregations, some of them carry-overs from German times, over and above the usual parish devotions: mass, rosary, benediction and occasional processions on the more solemn feast days. For young boys there were the Luistas and the Estanislaoistas, the congregations dedicated to St. Aloysius Gonzaga and St. Stanislaus, the Jesuit patrons of youth. Any boy could join the Congregation of St. Stanislaus providing he attended mass weekly, received communion twice a month, showed up for daily catechism class, and tried to lead a decent life. Members had the distinction of wearing around their necks large medals attached to wide blue ribbons. The Jesuit brothers moderated these congregations, meeting with members monthly to give them a homily on the importance of a good Christian life.  Congregation of San Luis gathered near the church in Kolonia Kitti, which had always been isolated from the rest of the mission by virtue of its remoteness, remained something of a backwater area during these years. Fr. Lasquibar, aging and increasingly infirm, lived at Wene with Br. Aguinaco to assist him. Despite his years, the pastor performed his regular parish duties and held religious instructions for the ten or 15 children he could muster each afternoon when the public school let out. Fr. Lasquibar was a recluse who almost never wrote to friends and family in Spain and seldom visited Kolonia. A Jesuit visitor to his parish remarked that he had taken on an ascetical appearance. He ate and drank very little, and he dressed in "threadbare habits that were held together with cord and looked like a pin-cushion more than anything else." He covered surprising distances for a man his age, leaning on an oversized staff and looking like the fabled pilgrim of Compostela. His people quaked when the priest started in on one of the fiery denunciations for which he was famous, but were relieved when the target of his polemic turned out to be Buddha, Confucius or Martin Luther rather than their own wickedness. For over 15 years this awesome priest presided over the Kitti parish. An Environment Grown Hostile Life on Pohnpei was changing perceptibly as the 1930s began, and not all of the changes were blessings in the eyes of the missionaries. For one thing, hundreds of Japanese colonists were streaming into Pohnpei to fish or work as laborers on the farms that the government was setting up in its efforts to boost commercial productivity. With the increasing number of Japanese and Okinawans, the government was making even stronger moves to Japanize the people through the schools and the other means at their disposal. The missionaries felt that the main concern of the government was becoming less the welfare of the island people than the advancement of Japanese social and economic interests. Then there was the growing number of jobs for Pohnpeians and the consequent boost in affluence, bringing with it the dangers of materialism and neglect of religion. Although the missionaries remained on friendly terms with the Japanese governor and his staff, they felt increasingly helpless in the face of the tide that they saw engulfing their people Despite the missionaries' fears, conversions continued throughout the early 1930s, and the number of Catholics in Pohnpei grew from 1,400 in 1921 to about 3,000 by 1934. There were even a few Japanese converts such as a woman teaching in the Kolonia government school who became a Catholic after reading the autobiography of St. Teresa that someone put in her hands. One of the priests thought that all this was owing to the missionaries' dedication to visiting the sick and dying, something that he felt had made a favorable impression on Protestants on the island. Yet it was the Pohnpeians themselves who were often the main instruments of conversion, as had been true from the very beginning. The wife of the catechist Luis Kiho, for example, had instructed a girl from Kapingamarangi in the faith, and she in turn converted several others in her family. It was not only the children who were leading their parents to the faith, but the catechists and devout adults who were bringing others to Catholicism. The Jesuits, in the meantime, were beginning to show the effects of their rigorous years on the island. Br. Burzaco, who had founded and run the small boys dormitory in Kolonia, was the first to die in late 1932. Fr. Dionisio de la Fuente, formerly working on Saipan, had come to Pohnpei to recoup his strength but suffered a severe stroke and finally died the same year. Two years later Fr. Jose Pajaro, who had worked on Pohnpei intermittently for a total of three years, also succumbed to illness as he was returning by ship from the Marshalls, and he was buried on the island. Meanwhile, Br. Juan Ariceta was transferred from Pohnpei to work at the Procurator's office in Tokyo. But there were new arrivals as well during these years. Br. Juan Belinchon and Br. Agustin Aguinaco came during the late 1920s to join the Pohnpei mission staff. Br. Belinchon was stationed in Awak to help Fr. Castro, who had once again begun serving as pastor there since Fr. Berganza's transfer to Kolonia in 1927. Two new Mercedarians were also added to the staff of the girls' school in 1930, one of them replacing Sr. Serapia, who left Pohnpei the same year.