|

|

| introduction | yap | pohnpei | chuuk | palau | marshalls | ||

|

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN YAP

A Foothold in the Carolines On June 29, 1886, the steamship Manila arrived at Yap from the Philippines after a voyage of eight days in rough seas. It carried the first Spanish governor of the western Carolines, Manuel de Elisa, a handful of Spanish officials, about 50 Filipino troops and their commander, and a number of Filipino convicts, to establish Spanish rule over these islands for the first time. It also brought six Capuchin missionaries, three priests and three brothers, who were to found the first Christian mission on Yap. The Spanish had come to Yap in August of the previous year to take possession of the island in the name of the king of Spain, but the German warship Iltis, although reaching Yap four days after the Spanish, had raised the German flag before the Spanish had unfurled theirs. The incident caused a controversy between the two countries that nearly led to war before the matter was finally left to the Pope to decide. When the papal decision was made in favor of Spain, Spanish authorities began preparing for the occupation of the islands in 1886. The rain fell in torrents during those days in late June as the supplies for the new government center and the mission were off-loaded from the Manila. The Spanish troops and the Filipino convicts hauled building materials, grain, and tents for temporary shelters, and led off the horses and cattle to the hastily erected stables. The site of the governor's residence and barracks was Tapelor, an island later purchased by the Spanish and connected by a causeway with the mainland. Here the seat of the government was located, while private houses were built up the hill towards Nimar. Meanwhile, the Capuchins arranged for the conveyance of their own supplies, as the downpour continued. At the dock to welcome the new missionaries was Bartola Garrido, the widow of an American trader who had lived with her husband for several years on Yap. Bartola, who was raised in Guam and educated by the Recoleto priests, was a staunch Catholic and a firm supporter of Spanish rule in the islands. The year before, after the Germans had claimed Yap, she had raised a Spanish flag that she herself had sewn in a show of patriotism. As she greeted the Capuchin missionaries at the dock, Bartola's face showed disappointment, for she had expected to see the Recoletos who had accompanied the Spanish party a year earlier with the intention of founding the mission. Since then, however, the Pope had entrusted the Caroline mission to the Capuchins. Bartola's disappointment soon passed and she presented the Capuchin with rolls, fish and other food with a promise of further assistance in the weeks ahead. The Capuchin were not the first to try to establish the church in the Western Carolines. Catholic missionaries had come on two occasions more than a century and a half earlier, but their attempts to plant the faith had both ended in failure. In 1710 two Jesuit priests were put ashore at Sonsoral by a Spanish ship, but they were never seen again and were presumed to have been killed by the local people. In 1731 another Jesuit, Fr. Juan Cantova, and his companion sailed from Guam to Ulithi where they founded a mission that prospered for a time. Fr. Cantova's companion was forced to return to Guam for supplies a few months after their arrival, however, and when he returned two years later he found that Cantova and the Spanish troops who were supposed to protect him had all been killed by the inhabitants and the mission buildings had been demolished. For the following 150 years no further attempts were made to establish a mission. The American Protestant missionaries who brought Christianity to the eastern Carolines and the Marshalls considered extending their work to Yap, but the added length of the voyage and the expenses involved discouraged them from ever doing so. It was only with the onset of Spanish rule that Christian missionaries came to stay. The Capuchins set up their quarters at the outskirts of the Spanish settlement, the colony known as Santa Cristina in honor of the patron of the Queen Regent of Spain at that time. This was located at the site of the mission today. For the first few days the missionaries lived in tents that were loaned them by the Spanish troops. Before long, however, they finished building the wooden house that would serve as their central residence. They also built a small church roofed in thatch that was named Santa Maria and an open building that could serve as their school. For a year the six missionaries lived together–Fr. Daniel Arbacegui, the superior, and two other priests, Fr. Antonio de Valencia and Fr. Jose de Valencia, together with three brothers, Br. Crispin de Ruzafa, Br. Eulogio de Quintanilla, and Br. Antolin de Orihuela.

Fr. Ambrosio de Valencia, Capuchin Superior Contacts between the missionaries and the Yapese were infrequent and guarded at first. The Capuchins went out in pairs each afternoon to visit people in nearby villages, particularly the chiefs. Often they spent their time instructing those they met in the new religion they preached. Children especially seemed attracted to the strange-looking creatures with their half-shaved heads and their long brown robes, and they would flit about the bearded Capuchins tugging at their cowls and laughing merrily. To anyone who came to the mission residence the Capuchins would give small presents: mirrors, cheap flutes, whistles, and particularly clothes. So frequently did the missionaries give away articles of clothing, in fact, that for a time Yapese people hesitated to visit the mission unless they were wearing Western clothing. All of this was done in an effort to gain the good will and acceptance of the people. From the very beginning the Capuchins devoted themselves to teaching the young. Any new mission station that was built in Yap (or later in Palau) always had its school building alongside the church or rectory. The Capuchins felt, as many other missionaries in other parts of the world often have, that they could more easily gain a foothold in society by working with children. In the first school, held in the simple thatch building in Santa Cristina, the priests and brothers did all the teaching. Classes were held each morning between 8:00 A.M. and 12:00 P.M. The school children spent the first hour practicing how to write in Spanish, and were then instructed in Christian teaching, geography and arithmetic. The morning ended with the recitation of the rosary and the singing of hymns to the accompaniment of the violin or accordion. Sometimes in the afternoon students would work in the garden or help the brothers in the carpentry shop. The education of girls presented more of a problem. At first Bartola was given charge of a small class of girls in Santa Cristina, while the Capuchins appealed to Spain for teaching nuns to run girls' schools. When, in time, it became clear that foreign nuns were unavailable, the Capuchins had Bartola recruit a few Guamanian women to teach in their mission schools.

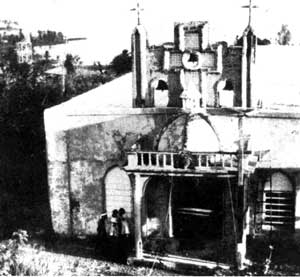

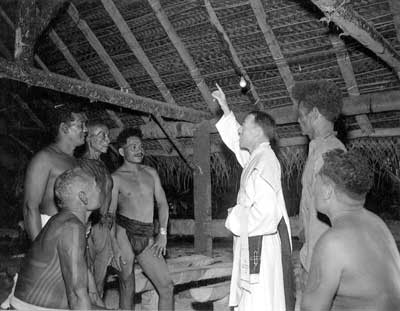

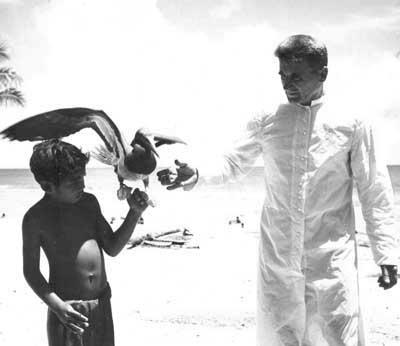

Sketch of the first Capuchin mission in Yap The patient work of the Capuchins during their first months in Yap finally bore fruit. On February 2, 1887, the first Yapese was baptized–a child who was given the name Leo in honor of the pope who had appointed the Spanish Capuchins to their new mission in Micronesia. The Spanish governor served as godfather in a solemn ceremony that was attended by the entire Spanish colony and many Yapese. Not long after this, 30 more Yapese, including several adults, were baptized. The missionaries were cheered by these events, just as they were by the unannounced arrival of the half dozen Capuchins en route to the new mission on Pohnpei. For three weeks the Capuchins enjoyed the unexpected reunion with their brothers destined for the east until they at last left on the Manila for Pohnpei. Within a few months a second church was set up, this one in Guror at the southern tip of the island. On July 20, 1887, the new church, a small, temporary structure located at water's edge, was formally dedicated to San Francisco, and Fr. Jose de Valencia and Br. Eulogio de Quintanilla were assigned to this new station. The Capuchins soon completed a comfortable two-story residence and, with the help of some of the Filipino soldiers, began work on a new church built of imported lumber and corrugated iron. The small congregation at daily mass donned western clothes for the service. The school began classes for as many as 17 students, and in the afternoons Fr. Jose would often wander over to the men's house to chat with the women staying there. Throughout the years of Capuchin work on Yap, the Guror church remained the most important station outside of Santa Cristina. Despite the apparent rapid expansion of the mission in its first year, the missionary work was slow and filled with frustrations. The difficulty in learning the language was one source of frustration, despite the publication of a Yapese grammar by Fr. Antonio de Valencia during this time. The missionaries complained again and again of the custom of mespil, or institutionalized prostitution, as well as of the widespread divorce and polygamy, although they soon recognized the futility of trying to eliminate these customs all at once. Above all, they regarded the temperament of the Yapese as one of their main obstacles. The people appeared to the missionaries as cool and aloof, stubbornly resistant to change and very slow to give up their traditional beliefs. The first major confrontation between these traditional Yapese religious beliefs and Christianity was not long in coming. An earthquake in Lamer in March 1889, the first in the memory of the people, lasted for three months and left the people of that vicinity shocked and terrified. This strange event inspired a prophetic movement led by seven men from that village who began collecting Yapese money of different kinds as an offering to the kan or spirit of that place. These spokesmen for the spirit soon began telling everyone that all the Spaniards, missionaries included, would be driven out of Yap or be killed by the kan. The same fate awaited any Yapese who did not renounce their belief in Christianity. The effect of all this was to frighten away those people who had been coming to the mission for religious instruction, until Fr. Daniel himself confronted the prophets and challenged them to let him speak to the kan. At this the men backed down and were forced to retract their empty threats. The same seven men from Lamer began a revival of a fertility cult at about this same time. They cleared a large area, erected a two-story Yapese house (the only one of its kind in Yap), and started holding dances in their village every two or three days in an attempt to strengthen the traditional religious beliefs. They attracted large numbers of women to the dances by spreading the word that any woman who attended would become pregnant soon after. Enthusiasm for this revival waned quickly, the missionaries reported, after the wives of five of the seven cult leaders died and several of the women who attended the dances had miscarriages or died in childbirth. Even after such triumphs, Christianity made very slow headway in Yap. By 1890 there were no more than a few dozen baptized Catholics and a total school enrollment of only ten children. The new Spanish governor, the fourth in as many years, apparently felt that the social reforms that the government had hoped for were moving too slowly. He took it upon himself, therefore, to compel parents to send their children to the mission schools under the threat of a fine. School attendance jumped immediately, of course. The governor also prohibited the sale of alcohol to Yapese in an effort to control some of the abuses that liquor had brought with it. Forty deaths were attributed to alcohol during the three years before the ban, and the missionaries reported seeing some men forcing rum down the gullet of a drunk as they made him promise to send more liquor from the other side of the grave. The governor also came to the support of the missionaries in their conflict with the people of Wanyan. After the Guror church was destroyed by a tidal wave in 1892, the pastor wanted to move to Gagil and build a new church in Wanyan. In their haste to get the project underway, the missionaries selected a site and moved in their building materials before they had secured the permission of the chief. The village chief, who resented the intrusion, had his people dump all the building materials on the beach. As soon as the governor heard of this, he summoned the chief, jailed him for his misbehavior and forced the villagers to build the church within a set time limit. Even with all its problems, the mission continued to expand during these years. In February 1891 another six Capuchins, three priests and three brothers, were sent to Yap to bolster the mission staff. The new arrivals were Fr. Luis de Leon, Fr. Toribio de Filiel, Fr. Luis de Granada, Br.Melchor de Gerona, Br. Joaquin de Masamagrell, and Br. Oton de Ochovi. The additional personnel allowed the Capuchins to send four of their number–to open the first mission in Palau in April 1891. From the very beginning the Capuchins had intended to start a mission there, and just a year earlier Fr. Daniel and Br. Antolin had sailed to Koror in one of O'Keefe's ship to find out what the Palau an people felt about the proposed mission. The mission headquarters at Santa Cristina had grown considerably in the few years since the arrival of the Capuchins. The small thatch-roofed church had finally given way to a stronger wooden structure with a tin roof. The interior had artistic designs and religious frescoes that were done tastefully enough to impress a visiting American Protestant. It was equipped with a small organ, and a German musical box for those occasions when there was no organist. Then as now the missionaries were obliged to do fund-raising for their construction, and they raffled off a bullock to provide a large part of the money needed for the new church. The Capuchins also had a small boat, given to them by the trader O'Keefe, with which they could visit other parts of the island.  Baptism of the first Yapese child Meanwhile, the missionaries continued to establish new stations in Yap. In January 1892 they moved out to Maap where they built the church of San Jose in Toruw, which was staffed by Fr. Luis de Leon and Br. Antolin de Orihuela. The following year they constructed the new station of Santa Cruz in Kanfay and opened a boarding school there that soon became the largest and most advanced of the mission schools. Fr. Jose de Valencia was transferred from Guror to take charge of the new station of Santa Cruz. These two churches and residences, together with those at Santa Cristina and Guror, were the major mission stations on Yap. Besides these, smaller chapels were erected: that of San Fidelis in Aringel in October 1891; that of the Divine Pastor in Malay in August 1891; another in honor of San Jose de Leonisa in Yinuf in June 1893; a chapel to San Lorenzo in Wocholab, Maap, in May 1893; and another to Santa Veronica in Wenfara, Rumung, in December 1893. None of these chapels seems to have been much used at the time, however, and the two in the north were not replaced after their destruction in a typhoon some months after they were built. At about the same time the church in Guror, which had been destroyed by the sea, was rebuilt. The new church was located in Machbob on the ruins of a temple to the local spirit Gopin, and the event was celebrated by a solemn procession and a dedication ceremony attended by hundreds. The last church to be established by the Spanish Capuchins was the one in Wanyan, which was dedicated to San Felix in 1897. This church, which had been the cause of a dispute when it was first built a few years earlier, soon became the center of another conflict. Wanyan was at war with its old rival, Gachpar, and fighting had gone on intermittently for more than a month. They called the residence "the house of peace" in the hopes that it would lead to improved relations between the two villages. Additional Capuchins missionaries were assigned to Yap during these years to staff the new churches and schools. In 1893 Fr. Gregorio de Peralta arrived and was soon assigned to replace Fr. Luis as pastor of the church in Toruw. In 1896 another five Capuchins came from Spain–Fr. Alfonso Maria de Morentin, Fr. Vicente de Larrasoaña, Br. Samuel de Aparecida, Br. Carmel del Real de Gandia, and Br. Jesus de Beniarres. Three other Capuchins who arrived in the western Carolines at the same time were dispatched immediately to Palau. By the end of the decade there were 20 Capuchins in all at work in the western Carolines, with five of them working in Palau. The new manpower made it possible for Fr. Daniel to visit Woleai and some of the other outlying atolls by Spanish gunboat in 1898. The priest could do no more than say mass on each island and greet the people in the short time he was there, but this was the beginning of evangelization in the outer islands. With the loss suffered by Spain in the Spanish-American war and the sale of the Carolines and Marianas to Germany by a treaty of June 1899, conditions in the mission took a dramatic turn. As well disposed as the new German administration was to the Spanish priests and their work, it did not use its civil authority to support their work as the Spanish government had done. The new government allowed people full freedom in deciding whether they would attend church or send their children to school. The effect of this new policy was disheartening for the Spanish Capuchins who had worked for 14 years in planting the faith. Their achievements had been significant during this time. More than 1,000 Yapese had been baptized into the church, and the mission schools had a combined enrollment of 542. There were five major mission stations on Yap. The first book in the Yapese language, a catechism written by Fr. Daniel, was published in 1899. With the changeover in the government and the loosening of controls on the people, the missions and schools soon emptied. School enrollment fell off from 542 to only nine in the final year of Spanish rule. Meanwhile, the Yapese priests and magicians, who had resented the intrusion of Christianity from the very beginning, banned attendance at church and visits to the mission residence under pain of bodily harm or sickness. Soon the churches were as deserted as the schools; the only ones who came to mass were the Chamorros living on Yap and a handful of foreign residents. The Spanish Capuchins persevered in their work under these trying conditions, but they could do no more than attempt to hold on to as many of their past gains as possible. Any expansion in such circumstances was out of the question. The loss of manpower had been rapid since the change in political authority. Three Capuchins had died in recent years: Br. Oton de Ochovi in 1898, Br. Jesus de Beniarres in 1899, and Fr. Jose de Valencia in 1900. Several others were sent to Guam, now under American rule and without priests, where they could carry on a more effective ministry than in Yap. Frs. Luis de Leon and Vicente de Larrasoaña were transferred there in 1901, and two others followed them soon afterwards. By 1903 there were only seven Capuchins left in Yap and another four in Palau. According to the mission report for this year, there were three main churches and residences on Yap with four more sub-stations. Santa Cristina remained the largest residence and mission headquarters, and the pastor of this church also visited the chapels at Aringel and Wanyan. The second parish was San Francisco in Guror, with sub-stations at Machbob and Malay. Finally, there was San Jose in Toruw, which was cared for by a brother during the absence of the priest. The remnant of the Spanish missionaries struggled on until the western Carolines was formally entrusted to German Capuchins by a decree of December 18, 1905. The following year, Fr. Daniel Arbacegui, who had been superior of the mission for 20 years, finally left Yap to return to Spain. With him went Br. Antolin de Orihuela, who had also been on Yap since 1886. The era of Spanish Capuchins work in Yap was over. Before they abandoned the field to their German co-religious, however, the Spanish missionaries at least had the satisfaction of seeing the number of church-goers rise again, even if the churches were never afterward as full as they had been in the final days of Spanish rule. The Child of Sorrow The first of the German Capuchins, Fr. Salesius Haas, arrived in Yap in 1903. Almost immediately he began teaching German language classes in the school at Santa Cristina. Most of his 25 students were Yapese who were being trained as policemen or Chamorros who had moved to the island under the Spanish. Two years later Fr. Salesius left to return to Germany because of sickness, but during his short time on the island he wrote a book on Yapese life and culture. Fr. Callistus Lopinot came to Yap in December 1904 to replace Fr. Salesius. The following year five more German missionaries arrived to begin their work there: Fr. Paulinus Borroco, Fr. Eusebius Lehmann, Br. Nilus Kampling, Br. Konrad Zerbe, and Br. Joachim Petry. The six missionaries staffed the two main mission stations of Santa Cristina and Guror, and visited the two sub-stations at Aringel and Malay from time to time as well. Frs. Callistus and Eusebius with Brs. Konrad and Joachim worked in the colony at Santa Cristina, while Fr. Paulinus and Br. Nilus lived in Guror. Meanwhile, the eastern and western Carolines were joined together to form a single unit and the mission was raised to the status of an apostolic prefecture in December 1905. The entire prefecture was placed under the authority of Fr. Venantius Duffner, a Capuchin working in Pohnpei. Two years later the seat of the prefecture was moved to Yap.  Br. Georg Schmitt and Fr. Irenaeus Fischer, arrivals to Yap in 1909 The German missionaries were obliged to begin the evangelization of Yap all over again. In 1906 there were about 500 Yapese registered as Catholics, roughly half of the number listed at the turn of the century. Yet even those who remained on the church rolls frequently abandoned all their religious practices. One of the priests reported that of the several persons in Kanif and Aringel who had been baptized in former years not a single one still attended church. The German priests attributed the large number of lapsed Catholics to the overeagerness of their Spanish brethren to baptize all comers. To avoid the same problem in the future, the German priests offered lengthy catechetical instruction before admitting any candidate to baptism. This often meant that of perhaps 20 persons beginning the series of lessons, no more than five would persevere until the end. Yap had been known as "the child of sorrow" of the Caroline mission right from the start. The people were very slow to accept the new faith and slower still to practice it, the missionaries remarked again and again. There were none of the mass conversions there that had occurred in Pohnpei and other parts of the mission. Converts were made laboriously one by one, with baptisms rarely exceeding 20 or 30 a year throughout the German period. Even those who did receive baptism were all too susceptible to the pagan influences of the social environment, the misionaries thought. The number receiving the sacraments was quite small, even for the modest-sized congregations that the priests had. A pastor would report for a typical year perhaps a single Christian marriage, one or two Christian burials and a few anointing.  Srs. Theresia and Fridolina with Yapese school children Because of the difficulty in converting adults, the missionaries were forced to rely heavily on schools as a means of influence on Yapese society. The German Capuchins, therefore, soon reopened the mission schools attached to the parishes. To assist them in this work they requested Franciscan teaching sisters from Germany. In January 1907 three Franciscan nuns arrived in Yap where they were welcomed at the ship by children singing German hymns and escorted to their newly built residence as the church bells rang out joyously. The sisters were Sr. Fridolina Geiger, Sr. Adelina Knörr, and Sr. Theresia Götz. Within a short time they were teaching geography, arithmetic, religion, sewing and needlework to girls in the Santa Cristina school, while the Capuchinss taught the boys. Courses included strong emphasis on the German language, which was subsidized by the government in the islands. On Saturday afternoons the school girls would walk to Santa Cristina to prepare for the Sunday mass. There they would exchange their grass skirts for dresses, attend rosary and evening prayers, eat their dinner with forks and spoons (at least while the sisters were watching), and sleep under mosquito nets in the sisters' convent. The older girls would pride themselves on their European appearance, one of the nuns noted in her report. After one of them covered herself with soap in the shower, she turned to the sister with a smile and said, "Now I am as white as the Europeans." The girls attended mass on Sunday morning and then sat through catechetical lessons. After games and a mid-day meal, the girls surrendered their dresses, which were packed away until the following week, and donned their grass skirts for their return to their homes. The sisters watched them leave with the uneasy feeling that their influence during the weekend would be undone by the surroundings at home. There was some reason for concern. The missionaries complained time and again that many of their girls left school when they reached sexual maturity and disappeared in the village never to be seen again. One priest, Fr. Sixtus Walleser, felt that nothing could be done about this, but expressed the modest hope that when it came time for them to marry, the former mission students would at least be comfortable enough in the presence of the priest to accompany their husbands for marriage instructions. Despite all the difficulties, school expansion continued throughout these years. The Franciscan sisters, who never numbered more than four, helped out in some of the other schools besides taking charge of the girls school in the colony. Fr. Sixtus, who had charge of the western part of Yap, opened a new school in Kanif and persuaded the chiefs of that village to recruit capable students and punish them when they did not attend classes. The result was a thriving school of 35 or 40 pupils whose attendance was excellent. Fr. Sixtus divided his time between the school in Kanif and another in Okau; classes were held four times a week in the former and three times weekly in latter. By 1911 there were eight schools on Yap, two of them at the colony, with a total enrollment of 267 boys and 98 girls. The number of German missionaries was much fewer than that of the Spanish Capuchins before the turn of the century. Although two new priests were sent to Yap–Fr. Irenaeus Fischer in 1909 and Fr. Sixtus Walleser in 1910–the total number of Capuchins on Yap remained about what it had been five years before. Fr. Paulinus Borocco, one of the original band that arrived in 1905, was still on Yap and would remain there for several more years. Fr. Venantius, the Capuchin superior who had spent several years on Pohnpei, was also working on Yap at this time. They were assisted by Br. Nilus Kampling, another of the first group of Germans to Yap and the only brother on the island. The four priests divided up the pastoral care of the island. Two of them lived in the colony and were responsible for the main parish at Santa Cristina; the third was pastor of Guror and took care of the southern part of the island; the fourth had charge of Aringel, Okau and other villages on the western side of the island. The other stations of Wanyan and Yinuf were visited only occasionally by the priests. Like the Spanish Capuchins before them, the German missionaries devoted part of their time to preparing written materials in the local language that could be used for the instruction of Yapese Christians. Between 1910 and 1912 they published in Yapese a book of prayers (Warwir ko meiwil), the translation of a bible history (Chep ni zozup), and the translation of a catechism (Katekismo ni machiben e Kristiano). One of the early converts, Garangmaw from Delipebinau, assisted them greatly in the translations when he was not going about catechizing people in the villages. In addition, Fr. Sixtus Walleser composed a Yapese grammar to assist new missionaries in learning the language and wrote several articles about various aspects of Yapese life. Missionary work on Yap was interrupted shortly after the outbreak of World War I when the Japanese, who were at war with Germany, seized Germany's possessions in the north Pacific in October 1914. The two Franciscan sisters still on the island were sent back to Germany about a year later, and Fr. Sixtus left Yap in 1916. The three remaining missionaries–Fr. Irenaeus, Fr. Paulinus, and Br. Nilus–continued their work despite the growing number of Japanese restrictions on their activities. They experienced serious financial difficulties since all outside sources of funding were cut off during the war. They had been forced to close all of their schools and were seriously limited in the amount and kind of pastoral work they could do among the people. Finally in 1919 the Japanese forcibly expelled the last of the missionaries, and the three Capuchins returned to their own country, leaving Yap without priests and brothers. The German Capuchin period on Yap was over. The Turn of the Tide Yap was abandoned, but not for very long. Within a year the Japanese government, in response to the people's requests for more priests, was negotiating with the Pope to have missionaries from a neutral country sent to Micronesia. The mission was assigned to the Spanish Jesuits by Pope Benedict XV and soon new missionaries were en route to the island to build on the foundation that the Capuchins had laid. On March 14, 1921, Fr. Jose Gumucio and Br. Ramon Unamuno arrived in Yap to re-establish the Catholic mission there. The Jesuits were well aware of the difficulties that their predecessors had experienced on Yap. In fact, the Jesuits at first decided that because of their limited manpower they would not send anyone there at all and concentrate instead on other places. Only a chance conversation with a German living on Yap aboard the ship bringing the missionaries to Chuuk convinced the Jesuit Superior that this decision should be reversed. The two Jesuits, who had been originally assigned to Chuuk, were given a quick change in assignment and were sent on the next ship to Yap. The Jesuits disembarked, like the Spanish Capuchins 35 years before, in a torrential downpour. The large concrete residence that the German Capuchins had built (now the Maryknoll convent) had lost its roof in a typhoon a few months before and the building was in disrepair. They had to huddle under thick blankets that night to protect themselves from the rain. But keeping themselves dry was by no means the biggest problem that the new missionaries faced. Their scant funds were soon depleted, and one morning Br. Ramon held up a copper coin and told his companion that that was the last of their money. Within a few days, however, the Japanese governor visited the Jesuits and presented them with a generous government subsidy for their work. This money supported them until the ship bringing help from Spain arrived a few months later. The Japanese officials on Yap were very favorable to the mission in the beginning. The Jesuits were invited to official receptions for Japanese officials, and the governor frequently paid calls on Fr. Gumucio and even attended Sunday mass on occasion. In addition, the Japanese authorities continued to provide a regular subsidy for the mission. The Chamorro people living on Yap were a further source of support for the new missionaries, for they served mass, cared for the church, translated for the Jesuits, and did whatever else was needed. Nonetheless, these first few years were trying ones for the Jesuits. Like the missionaries before them, they found it extremely difficult to make converts from among the Yapese people, and they saw many of those who had been baptized earlier drift away from their religious practices. As one of the Jesuits summed up the situation, "most of the people were pagans, many had abandoned their faith, and only a few were practicing Catholics."  Main church in Yap, built by Spanish Jesuits in 1921 After 1925 the missionaries detected a remarkable change in attitude on the part of the people of Yap. Suddenly the very people who had been so resistant to conversion for 40 years expressed a growing interest in joining the church. One of the highest chiefs on the island asked for baptism and shortly before he died told those gathered around him: "By this grey hair soon to go to the grave, I tell you to become Catholics because this is the only true religion." His children and their spouses were soon afterward baptized and given the names of Spanish kings and queens. Meanwhile, one of the most renowned sorcerers, a man from Gilfith, turned over to Fr. Espriella the tools of his trade and asked for baptism. In the early stages of the great typhoon in 1925 he was asked by the chiefs to use his magic to protect their houses, but these turned out to be the first buildings destroyed by the typhoon. The sorcerer's baptism took place in his own house, which was formerly taboo for people to enter under fear of death. While Fr. Pons cared for the routine parish needs of Santa Cristina, Fr. Espriella traveled tirelessly around the island preaching the gospel and attempting to build up Christian communities in the different villages. One of the first villages he visited was Guror, a place that formerly had a large Christian population but which had not had Sunday mass for 15 years. Fr. Espriella found that most of the old Christians had abandoned the practice of their religion and many of them had divorced and remarried, some several times. The priest said mass, baptized a few children, and spent the next few days taking a parish census of the Christians. Not long after this he spent several days in Rumung, where he found only one of those baptized earlier living a Christian life. At his arrival in Rumung he was greeted by the same chief who had welcomed the Spanish Capuchins many years earlier. In the course of his visit Fr. Espriella baptized several people and began instructions for many others who requested baptism. After two weeks the priest felt he had taken a big step towards building anew the Christian community there. Fr. Espriella also visited Wanyan, a village in which the Capuchins had set up a mission station. Only one of the original Christians had remained active in the church two years earlier, but by the end of the priest's visit there was a flourishing community of 70 Christians gathering twice a day for prayers and rosary. The Jesuits did not establish schools in Yap, as the Capuchins had done. The Mercedarian sisters, who began teaching on Pohnpei, Saipan and Chuuk at about this time, never set up a community in Yap. The missionary strategy of the Jesuits in Yap was to travel continuously to different parts of the island, while one of the priests remained in Colonia and provided for the spiritual care of the Christian community there. This proved successful, but perhaps only because the time had come to harvest what others had so painfully sown. Between 1925 and 1930 the Jesuit Superior reported 1,000 conversions on Yap; the number of Christians had increased from 400 in 1921 to 1,500 in 1930. Whatsmore, one of the Chamorros living on Yap had entered the seminary in Tokyo. At long last Christianity had come to be widely accepted on Yap. The church in Yap now had a small group of dedicated catechists who went about instructing their own people. Augustine Ayin from Amun was one of the earliest in Gagil. With him worked Bernardo Figir of Wanyan, who had been baptized on Pohnpei on a visit to collect shells in 1923. Figir, the first person from Gagil married in a Christian ceremony, moved around Tomil, Gagil and Maap preaching and catechizing. He also acquired the land for the church that would be built in Wanyan during the 1930s. Other catechists active at this time were Defan in Rull and Tithin in Kanfay. Yapese Christians were bearing increased responsibility for preaching the faith to their own people. The Gospel Reaches the Outer Islands No sooner had the missionaries tasted their first real success on Yap than they turned to the outer islands to bring the gospel there as well. In February 1928, Fr. Bernardo Espriella began a six-week field trip to Ulithi. He was the first priest to visit Ulithi in 30 years, and the first ever to touch at any of the atolls beyond. Fr. Espriella first went ashore at Asor, where he stayed in a canoe house and said mass in a small building that served as the island school. Within a few days he was invited to Falalap by the chief of that island, who claimed that many of his people wanted to become Christians. Nearly the entire population of Falalap greeted the priest at his arrival and soon catechetical lessons began in a large canoe house. Since the priest knew none of the Ulithian language, instructions followed a simple format everywhere the missionary went. First he would show the people large posters on the central teachings of the faith, explaining what he could through an interpreter, and then he would begin teaching them basic prayers that had already been translated into the local dialect. Fr. Espriella wrote that he could barely keep back the tears as he listened to old men reciting these prayers again and again along with the little children. The people were so interested in the new religion that it instantly became the single topic of conversation on the island, and the priest answered questions on the differences between Christianity and the traditional island beliefs until 11 each evening. After two weeks instructions were going so well that Fr. Espriella held the first baptisms: more than 50 people in three days, including the island chiefs and a few of the local sorcerers. On one of these days he organized a religious procession, complete with home-made banners and Ulithian hymns, in honor of Our Lady. The procession ended at a large tree that the people of the island had regarded as sacred; the priest planted a large cross in the ground near the tree, sprinkled the area with holy water, and took out a small hatchet and chopped at the tree a few times. The Falalap people, now freed from the ancient fear of touching the tree, promised that they would finish cutting it down and would make it into a canoe that could be used for taking the priest around to the islands in the lagoon. The missionary's initial reception at Mogmog was by no means as enthusiastic. Espriella was not offered a house and had to sleep on the beach and say mass there on a makeshift altar. In time, however, a crowd of interested adults and children gathered around to look at the religious pictures, and the first baptisms were administered a few days later. The man responsible for this sudden change in the people's disposition was Mangmai, who had lived on Saipan where he had worked with the German Capuchins for some years. At Espriella's arrival on Mogmog, he began proselytizing among his people and soon became the priest's chief catechist in Ulithi. Hachegemang, one of the first converts, assisted him in this work for the next several years. So successful were they that the island chief, a paralytic, had his family carry him to the canoe house to hear the catechism lessons each day. When Espriella left the island a week later, a long line of people stood on the shore to kiss his hand and bid him goodbye. After short visits to Asor and Fasserai, where dozens more were received into the church, Fr. Espriella returned to Yap to begin planning his next visit to the outer islands. The priest had the good fortune to have found a group of dedicated Ulithians who would serve as the foundation of the church communities in that atoll and the missionary band to carry the gospel to further islands in the area. Mangmai soon went to Yap to do translation work for Fr. Espriella, while Hachegemang assumed leadership over the Mogmog church. On Fasserai the chief catechist was Yagmo, a blind man, who like Mangmai had spent some of his younger years on Saipan. From Falalap came Miguel Ylur, who was catechist there until after the war. Back in Yap Espriella recruited Manglol, originally from Asor, to help in translating catechetical materials and to assist him in future voyages. A year and a half later Fr. Espriella boarded a ship and fought the violent seasickness from which he always suffered to return to the outer islands. He spent a day in Ulithi, where he found his newly converted Christians fervent despite the opposition of the pagans; but his real destination was Fais, an island that had never been visited by a missionary. There he spent five weeks gathering people whenever he could to explain the mysteries of the faith and visiting the chiefs to win their good will. But the resistance to Christianity on Fais was deep-rooted, far more so than in Ulithi, and Espriella made only about 30 conversions during his stay. Some of the Yapese chiefs, it seems, had sent a warning to the Fais people not to be baptized. In fact, the son of a Yapese chief, who was there during Espriella's visit, was going around passing this word to the people and only stopped doing so when the priest threatened to have him arrested for impeding his work. Then, too, there were the island religious beliefs, which the missionary found even stronger on Fais than on other islands in the area. On full moon nights the island sorcerers gathered at the site of an ancient spirit house, where four stone pillars remained, to practise magic and invoke the spirits. During the final days of Espriella's stay on Fais the most famous sorcerer on the island died and several taboos were imposed on the people. People were forbidden, among other things, to cut down trees for a full year, with the result that the priest found it impossible to get the church built that he hoped to have underway before his departure. Instead, the priest used a small house as a chapel, set up pictures of the Sacred Heart and the Blessed Mother, stocked the chapel with a supply of holy water and Ignatius water, and left his few converts to the care of the Lord. In 1932 Fr. Espriella made another and longer trip to the outer islands, visiting distant atolls that had not yet been evangelized. After passing through a severe typhoon at sea that drove the ship 400 miles off course, the priest stopped at Faraulep for two days and baptized ten people. At Sorol, the next island visited, the single family living on the island told the priest they did not want to be baptized. Later in the course of his travels, Fr. Espriella spent a few days on Ifaluk where he found the people fearful because of recent cases of spirit possession. He was brought around the island to bless certain dangerous sites in the hope that this would drive off the demons that were believed to be infesting them. The missionary also spent a few hours on Eauripik, but without any real results. The principal object of this visit was Woleai, where he stayed for three months. Here the priest again ran into strong opposition from the chiefs, who did everything they could to prevent their people from accepting the new faith. Espriella noticed that the men were especially susceptible to the influence of the chiefs: at catechetical sessions they would remain in the back of the canoe house showing no more interest than an occasional glance at the priest, and on the road they would deliberately try to avoid the priest. Even so, however, there were some conversions, perhaps 50 or so, and a small group of Christians was formed to say the rosary each evening. Without any hope of preparing large numbers of baptism, Fr. Espriella spent idle days attending to simple needs: sewing his habit, washing his clothes, and making the soup that he ate each day for lunch. Finally, four months after setting out for the atolls, he returned to Yap. Confronting New Problems During the early 1930s Yap was beginning to change under the impact of Japanese modernization programs. Yapese, who were considered the best workers in Micronesia, were sent away in increasing numbers to labor in the phosphate mines on Angaur and Fais. Still others were recruited to work in the plantations of Pohnpei, where a sizable community of Yapese soon sprang up. The separation of men from their families for long periods of time had undesirable effects on the stability of the family, the missionaries complained. The Japanese public schools were also expanding through these years and attendance was made compulsory. The result of this was that the priests were unable to gather young people for catechetical instructions except for a few weeks during the summer. The number of Catholics in Yap had grown greatly as a result of the wave of conversions during recent years, but the priests faced the problem of instructing their converts and providing for their growth in the faith. In the past the main obstacle to the establishment of the church in Yap had been the old customs and beliefs. Now the missionaries recognized another serious obstacle: the new values and beliefs that were becoming widespread as a result of growing modernization. The final changes in Spanish mission personnel were made during the early 1930s. In 1933 Fr. Luis Blanco, the last of the Spanish Jesuits to be sent to Yap, arrived; and a year or two later, at the completion of his term as mission superior, Fr. Juan Pons left Yap to begin an assignment in the Marianas. Fr. Espriella, who was afflicted with beriberi and unable to get around as he did before, was sent to Wanyan to rebuild the church there and establish a residence with the help of the catechist Figir. Fr. Blanco was given charge of Santa Cristina and had the added responsibility of visiting the outer islands from time to time. Br. Francisco Hernandez remained in Yap at the Colonia residence to care for the material affairs of the mission.  Fr. Bernardo on his bicycle in front of the Colonia Church The two priests, one in Colonia and the other in Wanyan, were able to cover the whole island between them, thanks to recent improvements in transportation. The Japanese had finished deepening the canal built by the Germans, and a road system around the island was rapidly progressing. The missionaries received from benefactors in Spain a motorboat, with which they could reach even Rumung and Maap by sea without going outside the reef. As the road improved, both priests bought second-hand bicycles for calls to less distant spots on the island. The all-day walks to distant villages were a thing of the past, and even the most remote parts of the island had now become accessible to the missionaries. In 1936 Fr. Espriella reported that he visited Muyub, a village that had not seen a priest in almost eight years, and brought the sacraments to many of the old people who could not travel to Wanyan for Sunday mass. While on Rumung shortly afterwards, he stopped at several villages to instruct and baptize people and care for the sick. The priests still encountered some resistance and sometimes even open hostility from the people, especially in villages where there were few Christians. When Fr. Espriella went to Leng in Gagil to visit a dying girl, the girl's relatives ordered the girl to tell him that she did not want to be baptized. The priest left with a heavy heart, but one of the Christian women from a nearby village later saw the girl and persuaded her to be baptized just before her death. A year or two later the same priest was rebuffed as he went to the bedside of a boy who had been baptized some years before. Despite the family's insistence that Yapese could take care of their own at the time of death, the priest anointed the boy. After the boy's death his parents softened in their feelings, built a beautiful tomb decorated with crosses, called the priest in to bless the grave, and professed their desire to become Christians. One of the most remarkable apostles of Christianity during these years was Katarina Laetman, an old woman from Teb, a village in Tomil that had not been particularly receptive to the faith up to that time. For years this valiant woman had paddled her little canoe across the bay, in fair weather and foul, to attend mass at Colonia on Sundays and holydays. She had to brave far more than the weather in doing so, for the men of her own village would insult and deride her whenever she passed within hearing distance of one of the men's houses. Yet she never stopped making the trip and always begged the Christians in Colonia to pray for her people at mass, sometimes bringing the children a basket of delicacies in exchange for a promise of their prayers. In her zeal she never lost an opportunity to speak to her own people of Tomil about her faith or to help them when they needed assistance of any kind. She was a driven woman, so much in a hurry that she frequently ate bananas before they were ripe. Because of this the Tomil people would taunt anyone eating unripe bananas with eating "the food of Christians". Her deep love of God and her people, even in the face of scorn and opposition, eventually had an effect on the hearts of the people from Tomil. She always said that the very people laughing at her would become Christians sometime in the future. After her death shortly after the end of the war, the results of her efforts became obvious as the people of her area began entering the church in large numbers. Little by little the final resistance to Christianity was crumbling. In 1936 the chief of Maap asked to be baptized and the event was celebrated with a great feast. Many of the sorcerers, who had once held out strongly against the new religion, were also becoming Christian even though this meant that they could no longer accept gifts for the practice of their trade and their source of income was cut off. A well-known sorcerer by the name of Jose Leden, who was received into the church a few years before, gave a dramatic witness of his rejection of the old beliefs. When the workmen on a new road refused to touch a large boulder that they believed was cursed, Leden took the tools in hand and broke the rock into pieces by himself. When no misfortune befell him, the rest of the workmen were convinced that Leden was more powerful than the demons themselves Meanwhile, Fr. Espriella proceeded on the construction of the new church in Wanyan. With the permission of the Japanese governor, he salvaged some of the steel used in the old German cable station and started preparing the structure for a concrete building. The cement that Espriella had stored near the church site was destroyed in the typhoon of 1934, but the priest soon replaced it with the help of his friends in Spain. Working with a group of men from the village, Espriella finished the cement work on the structure and held the dedication of the new church on the feast of the Assumption in 1937. The church was octagonal in shape and the rectory was built over the church. Since there were no statues in the church and it was impossible to procure them from abroad due to the civil war in Spain, Espriella made his own. Mixing cement with different types of soil to produce various colors, the priest molded three four-foot high statues for the altars in the church. The result of his work surprised him and led to a flurry of questions from his parishioners about the saints who were represented.  Fr. Espriella in front of his new church in Wanyan Shortly after the completion of the church, the chief of Gachapar was converted to Christianity. The old chief, scarcely able to walk but still one of the most influential persons in Yap, had rejected offers of baptism for a long time, since he blamed the new religion for the many epidemics and the continuing population loss on Yap. One day, however, he presented himself to the priest and said that he wanted to learn about Christianity. He began attending mass on Sundays, always leaving a gift on the altar and speaking aloud to God on entering and leaving the church. Several weeks later, after his instructions were completed, he was baptized and received his first communion during mass. Afterwards a large feast was given in his honor and attended by 300 people. From that time on the chief attended mass each morning and rosary each evening despite his age. While Fr. Espriella cared for the northern and eastern parts of Yap, the outer islands were not completely forgotten. Fr. Luis Blanco made a trip to Ulithi in 1934 to add to the size and strength of the small Christian community there. He found that the women in Ulithi had begun to disregard the taboo against leaving menstrual houses during their monthly period so that they could attend religious devotions. Still, he had very little success in converting the remaining pagans to Christianity. One of them told him that he did not want to be converted because that would make it more difficult for him to go to hell where he hoped to meet his parents after his death. There were other trips during the late 1930s, three during 1937 alone to Ulithi, Fais and Ifaluk. Fr. Blanco's long trip in 1938, however, was the most significant because it brought him to Lamotrek, an island that still had not been visited by any missionary and that lay almost at the farthest edge of the Yap outer islands. The priest was disappointed at first that his Ulithian catechists could not accompany him, but he was relieved to find the people on Lamotrek very receptive to his teaching. Any difficulties that he experienced seemed to vanish providentially. An old woman who scoffed at the Christians by making the sign of the cross on her back was soon struck by a terrible pain in her back that left her dead within two days. A Japanese working as a manager of the Nanyo Boeki store who refused to give permission for his son's baptism and imposed especially heavy work loads on converts suddenly disappeared; his body turned up at the bottom of a cement water tank where he had drowned himself in remorse for sending away his wife. His son was subsequently baptized and given the name Lucas. Ramon, the island chief, refused to allow women to enter the church during their menstrual period until he was struck with a severe case of asthma and repealed his ban. When Fr. Blanco left Lamotrek after three months on the island, he had baptized nearly half of the population along with four young people from Satawal, whom he hoped would return to their own island to spread the faith there. This was the last trip made by any of the Spanish Jesuits to the outer islands due to the stringent restrictions on travel imposed by the Japanese. Much remained undone, but the priests had left over 400 Christians and seven chapels scattered throughout the atolls of the area. The continuing problem, of course, was how the missionaries might assist their converts in maturing in their faith. There was not the means to train catechists for the islands, and the priests could not spend more time there without neglecting other duties. As a half-measure, the priests invited some of the young men who were attending school on Yap to live with them in the hope that at least some would be moved to return to their islands as catechists in time. As war became imminent, the missionaries found themselves increasingly hampered in their work. The attitude of the Japanese government towards the Spanish Jesuits, which was once supportive even to the extent of subsidizing the mission, grew more hostile by the day. From the late 1930s on, Japanese police visited the mission to conduct interrogations regarding the Jesuits' activities and the sources of their financial support. With the mobilization of local men and women to work on military fortifications and other projects, the missionaries found that almost everyone except themselves was busy all day long. They did what they could in the evenings–they visited families, gave religious instruction in preparation for the sacraments, and offered week-long evening retreats. They also continued to hold intensive catechetical classes for the public school children during their vacation months. The rhythm of life rotated around the Japanese war effort and the missionaries had to schedule their activities around this. In time the Jesuits had even more severe restrictions put on their travel, and they were forbidden to teach and preach in any language other than Japanese. Meanwhile, the priests were unoccupied most of the time. Fr. Espriella complained that at Wanyan for lack of anything to do he spent the day washing his clothes, making bread, doing a little masonry on the residence and tending a small garden. By 1941 the Jesuits had been working in Yap for 20 years; in the course of their work over 2,000 of the island's population of 3,000 had become Christian. The numbers were impressive. Yet at the very time that the communities needed instruction and support the missionaries were able to do little more than pray for their people. The church of Yap was now in the hands of Yapese catechists for the first time. During the long confinement of the priests, they continued instructing people, witnessing marriages, and gathering villagers for prayers whenever possible. The war was the first real test of their mettle.  (from left) Fr. Luis Blanco Suarez, Fr. Bernando de la Espriella, and Br. Francisco Hernandez, all killed by the Japanese during the war Finally, in July 1944, as the Japanese prepared for an American invasion, the three Jesuits on Yap were sent to Palau by the Japanese military police. Through the summer months they lived in an isolated spot on Babeldaob together with two priests and a brother working in Palau and a Filipino and his family who had been employed in an observatory on Yap. Like everyone else at that time, the Jesuits suffered from the shortage of food despite the best efforts of some Catholic families in Palau to smuggle sweet potatoes to them. Suddenly, on the evening of September 18, 1944 a truck manned by Japanese police pulled up to the house; the prisoners were loaded into the truck and driven off to an even more deserted spot. Fr. Blanco, Fr. Espriella and Br. Hernandez, along with the three other Jesuits and the Filipino family, were ordered out of the truck and were forced to kneel alongside a large trench where they were shot at close range by the Japanese military police. Their bodies were later dug up and cremated, but the gravesite remains unknown to the present day. Out of the Ashes The Christian communities in Yap had to maintain their faith and their religious life with almost no help from foreign priests for the duration of the war and a year afterward. It was only in December 1946 that Yap was again visited by a priest. Just a few months before, the mission had undergone a major change in status: the Marianas were taken away and made a part of Guam, and the Caroline-Marshall Islands were transferred from the Spanish Jesuits to the American Jesuits. Within another year they would be entrusted to the New York Province of the Society. Fr. Edwin McManus, the first American Jesuit after Fr. Vincent Kennally assigned to the mission, visited Yap for ten days to provide what pastoral care he could and to survey the damage done by the war.  Chaplain James E. Norton explaining to natives work required on roof of Doughboy Chapel at Ulithi: 1945 Fr. McManus was impressed with what he found. Although the people knew nothing of his visit beforehand, over 200 had gathered at the bombed-out church in Colonia on Sunday morning to recite the rosary, as they did every day. The priest said mass and spent the rest of the day–until 9 P.M.–hearing confessions, blessing marriages, and baptizing and confirming children. During subsequent days he went from village to village where he found many unbaptized adults who wanted to become Christians. Working through an interpreter, he tried to re-establish some of the church structures that may have been lost through the war years. New catechists were appointed and plans were made to instruct those who wanted baptism. The people's fervor was high, but church buildings had suffered greatly during the war. The church and residence in Wanyan built by Fr. Espriella had been used by the Japanese as a military depot and had been all but demolished by American bombs in the last years of the war. The old concrete residence in Colonia had been severely damaged but was not beyond repair, while the church there was in ruins.  Fr. Fred Bailey blessing a Yapese child A year later, in September 1947, Fr. Fredrick Bailey arrived as the first resident American priest in Yap. He lived in a small quonset hut and said mass first in the former house of the Japanese governor and later in the cell ar of what is now the Maryknoll convent. The small church that he set up in Colonia was soon destroyed in a typhoon, but it was replaced by a double quonset hut that survived the next few years. Br. Gregorio Oroquieta, who had spent 25 years in the Marianas, arrived in Yap in September 1948 to take up his new assignment. Like all the Spanish brothers, he did anything and everything that was needed for the care of the mission property. Within a short time he had put in the foundation for a new concrete church in Colonia and had made extensive repairs on the old German-built house, which was being readied for Maryknoll Sisters when they were available for Yap. Two chapels in other villages were also restored and Fr. Bailey began making regular visits to the villages just as the priests before him had. When the 200 Chamorros who had lived on Yap for over 50 years were relocated in the Marianas in 1948, the Yap church lost a significant portion of its membership. Yet it also gained the freedom to be a church for the Yapese people for the first time in its history. A new generation of Yapese catechists had come to maturity during the war and were now serving the needs of their church. Joseph Yug, who had become interested in the faith while recuperating from tuberculosis before the war, traveled throughout Gagil and Tomil giving religious instruction and preparing people for the sacraments. Matthew Mar, later to become one of the first deacons, began an active ministry in his own Delipebinau. In time he was not only teaching catechism to the students of village schools but also accompanying Fr. Bailey on his pastoral visits and preaching after mass. He also helped in the rebuilding of the Colonia church and did the major work in the construction of the new church in Delipebinau. The chief catechist during these years, however, was Pagel, a free spirit who moved throughout the entire island preaching and teaching the faith. Like the disciples in the gospel, he traveled without a purse and staff, stopping wherever there was need and eating from the same pot as the low caste people he catechized. Although the church in Yap was slowly being rebuilt, the outer islands remained largely neglected until the arrival of Fr. William Walter in February 1949. Fr. Bailey had made only one quick trip to some of these islands the year before, the first visit by a priest in ten years. In Fr. Walter, however, the outer islands were to find a devoted pastor for the next 27 years. From the very beginning Fr. Walter put great emphasis on the construction of churches on the different islands, for he found that on islands where churches or chapels existed the people would gather three times a day to recite prayers. On islands that had no church, on the other hand, people were poorly instructed and less devout. Hence, his church construction program for the outer islands was intended to improve catechesis and the spiritual life of the people.  St. Mary's School in the 1960s: registration day Yap acquired another American priest with the arrival of Fr. Francis Cosgrove in 1951. He and Fr. Bailey divided the work on Yap proper, and new mission stations were opened in the villages outside of the district center. The new church of St. Catherine's was dedicated in Tomor, Tomil, and mass was said there every Sunday and holy day. Chapels were also set up or repaired on Maap and Rumung. Not all the efforts were focused on churches, however. Fr. Bailey began intensive work with families to develop family prayer and devotions; "every family is a church" was the motto he used as a statue of Our Lady circulated from one Yapese home to another for a week at a time. He also inaugurated in the villages the weekly Friday evening holy hours at which men would renew their promise to abstain from achif and other alcohol.  Graduating class of 1968 Soon Yap had its first mission school in 40 years. In 1953 St. Mary's School in Colonia was opened under the direction of three Maryknoll Sisters: Sr. Irene Therese, Sr. Fidelis, and Sr. Francis Xavier (who is still working in Yap today under her own name, Sr. Joanne McMahon). The sisters were installed in the present convent, the old German rectory; they taught classes in the basement of the same building and in a rundown quonset hut. Lack of materials and trained teachers were ordinary problems in the running of the school, but there were other difficulties as well. Children had to come from great distances to attend classes each day, and the influence of the school over students' lives was limited to the few hours a day they were actually on the premises. Plans were tentatively made to set up dormitories for the school children, but the part of the mission property on which the dorms were to be built was still being held by the government. The dormitories were never built, of course, but a small building was soon put up to house boys from the outer islands attending St. Mary's School. The American Jesuits hoped, as did the Spanish priests before the war, that some of the boys would return to their islands after schooling to become catechists and religious leaders among their own people. Within three years of the opening of the school, three girls and five boys had graduated, one of whom went on to attend Xavier High School in Chuuk. Further school expansion was envisioned. Within a few years, a new cement house was built at Colonia as a home for an American volunteer couple who were to teach at St. Mary's School. Plans were also made to open a second school, this one at Tomor in Tomil, at the site of the church that had been put up a few years earlier. Lack of teachers and funds finally forced the Jesuits to abandon these plans, however. Parish work continued and the number of Christians increased, even as changes in personnel occurred from time to time. Fr. John Condon arrived in late 1957 at about the time Fr. Cosgrove returned to the US. Within a year, Fr. Condon was appointed the superior of the Jesuits in Yap and the pastor of Colonia. By 1959 the number of Catholics on Yap had reached 3,400 out of the total population of 5,500. There was a growing group of zealous catechists for the villages, and the first two girls went off to Saipan as aspirants for the Mercedarian Sisters.  An island-wide procession for the feast of the Queenship of Mary Gains were even more impressive in the outer islands, where Fr. Walter visited every island three or four times a year. The Spanish priests had laid a good foundation for Christianity on some of the islands, especially those they had visited frequently or for a longer period, such as Ulithi, Woleai and Lamotrek. Many of the other islands, however, had only small minority of Christians who were hounded by their chiefs because of their opposition to many of the ancient customs. Christians, for example, would not participate in the community ceremonies to propitiate the gods of the sea before canoes set out to fish. Such was the situation in places like Sorol, Ngulu, Ifaluk, Faraulep and Satawal in the late 1940s as Fr. Walter began his work in the outer islands with the help of Joseph Hasedol and other catechists. The next five or six years saw some surprising changes on those islands, however. Sorol, which had no Christians at all in 1949, had half of its population baptized a few years later. On Ifaluk, where there were only five Christians formerly, one hundred people had been baptized in a single year; the atoll soon had two churches and a Christian majority of the population. Faraulep was a similar story: 45 people sought baptism in 1952, and the island soon had over a hundred Christians. The institutional changes that accompanied these conversions were no less surprising than the conversions themselves. An old man from Ngulu by the name of Antonio had insisted that his body be buried on land rather than at sea, the customary mode of burial, and the island chiefs were forced to consent. The chiefs of Ifaluk, despite their fear of natural calamities if old burial customs were not followed, yielded to Fr. Walter's request to allow land burials. The isolation of women in menstrual houses during their monthly period was also falling into disuse on many islands, because women could not otherwise attend church for daily prayers. The priest also noticed that island magicians and medicine men who died were not being replaced on those islands with predominantly Christian populations.  Fr. Jake Walter, missionary to the outer islands for 25 years, shares a pet with a friend By the late 1950s the outer islands had been essentially christianized. There were still pagans, sometimes a significant minority, on some of the islands, but the Catholic religion had become the prevailing force in island life. The conquest of the outer islands was best symbolized by a voyage to these islands that Bishop Kennally made in 1960, three years after his ordination as bishop. The voyage on the mission schooner Star of the Sea ranged over 2,600 miles and covered all the major atolls of the area. This was the first time that the island people had ever been visited by a bishop. Even the fury of typhoon Ophelia, which devastated the islands just a month later, did not diminish the new-found fervor of the people. In each of the islands of Ulithi the people found refuge from the storm in the newly built concrete churches, and on Asor they were forced to huddle around the elevated altar to escape the rising sea that flooded the very floor of the church. In the end they were spared their lives despite the destruction of all their houses and property, and Fr. Walter's church construction program was vindicated once and for all. Beyond Conversion In Yap proper the church had come to a turning point by the early 1960s. With more than three-fourths of the population now baptized, the era of primary evangelization was over and more attention was turned to deepening the faith in those who already professed it. There was the further task of adapting church structures and popular piety so as to conform to the new theological currents that had been accepted by the Second Vatican Council. With its emphasis on the church as a sign of salvation and a servant to the world, missionaries could not be content with merely making conversions and nurturing their personal piety. The church was to be a beacon light even for those who remained outside it. There were other changes to be implemented as well in keeping with the liturgical reforms and the call for more lay participation that were issued by the Council. It was left to Fr. John Condon to deal with these new problems as best he could, for Fr. Bailey was forced to return to the U.S. for health reasons in 1964. Another Jesuit, Fr. Paul Barrett, was assigned to Yap in the same year, but he left within ten months. For the next few years Fr. Condon was the only priest regularly occupying the new concrete rectory that had been completed in 1963. The 1960s were also a period of rapid educational expansion in public schools and private. St. Mary's School developed from its humble origins into a school of over 200 elementary students, and in time the ramshackle quonset hut that served as a classroom building was replaced by the present building. Sr. Ann Dowling took over the principalship of the school, while other Maryknoll Sisters came to serve as teachers. They were joined by several Yapese, some of whom remained in their teaching position at St. Mary's for years. In more recent years Notre Dame sisters from Guam have also generously assisted in the work of the school. Some of the more able graduates of St. Mary's were sent on to Xavier High School or PATS to pursue academic studies or vocational training in a Christian atmosphere. Among those who went on for high school were John Rulmal, Nick Rahoy and Apollo Thall, and Cuthbert Yiftheg, all of whom later entered the seminary and were eventually ordained as deacons or priests. The brighter girls often went on to private high schools on Saipan or Guam to finish their high school. There were vocations to the sisterhood from this group: Sr. Walter Marie, now in the Notre Dame Sisters; Sr. Rosemary, who entered the Carmelites; and Sr. Margou, now working in Yap. In time, then, the old hope that the Catholic schools would become a seedbed of vocations began to be realized.  Fr. Neil Poulin and Br. Gregorio Oroquieta inspect Kanfay church construction in 1968 The church on Yap was given new impetus with the coming of additional personnel from the late 1960s on. Fr. Neil Poulin arrived in 1968 to assist Fr. Condon, and Fr. Jack Walsh came out the following year to help Fr.Walter in the outer islands. In 1973 Fr. Paul Horgan also came to Yap to replace Fr. Condon, who was transferred to Guam. Br. Gregorio left in 1971 after 23 years on Yap and 50 in the mission. With two priests working on Yap proper and another two in the outer islands, the mission staff was at full strength once again. For the next several years, Fr. Poulin worked as pastor of St. Mary's and took responsibility for the main island, while Fr. Horgan cared for Tomil and Gagil along with Maap and Rumung, with the church in Tomor, soon after renamed St. Peter Chanel, as his main church. Later, in 1981, they switched parishes, with Fr. Poulin living in Gachapar. Meanwhile, a number of new programs were begun. Weekly religious radio programs were produced; catechetical programs for the entire island were begun by Sr. Joanne McMahon; and in time weekly prayer groups were started for adults. At this time, too, the pastors began training the first candidates for the diaconate on Yap.  Young Micronesian priests posing with Bishop Neylon at the ordination of Fr. John Hagileiram in 1985; (from left) Fr. Nick Rahoy, Fr. Apollo Thall, Bishop Neylon, Fr. John Hagileiram, Fr. Julio Angkel One of the strong emphases throughout the mission since the late 1960s was the indigenization of the church. There was growing concern to assist the church in becoming truly a local church under local leadership. The ordination of the first Yapese deacons in 1975, six in number, was a big step in that direction. Still another was the double ordination on Ulithi in 1977, when John Rulmal was raised to the diaconate and Nick Rahoy became the first person from the Yap area ever to be ordained a priest. Fr. Walter never lived to see the ordination, for he died of throat cancer in late 1975, but he would have rejoiced that his successor as pastor of the outer islands was one of his parishioners. Fr. Rahoy's ordination was all the more timely since Fr. Walsh left the mission soon afterward. Within two years, Fr. Ken Hezel was sent to Ulithi to assist in setting up a program for the training of outer island catechists, something that Fr. Espriella would have liked to have done 40 years earlier. With the ordination of Fr. Apollo Thall in 1983 and his return as an assistant pastor, Yap proper now had a priest from among its own people. The ordination of John Hagileiram from Eauripik in 1985 and Cuthbert Yiftheg in 1989 gave Yap a total of four local priests. A fifth, Kenneth Urumulog, was just ordained a Jesuit in 2002. In all, a strong beginning has recently been made in indigenizing the church in Yap. It has been more than a century since the steamship Manila put the first Spanish Capuchin missionaries ashore on that rainy day in June. Dozens of foreign missionaries–priests, brothers, sisters and lay volunteers–have followed them to Yap to make their own hidden contribution to the growth of the Yapese church. Through their efforts, together with those of many "apostles" from among the Yapese people, the church was slowly established in these islands. With faith these pioneers faced the discouragement and frustration of their work as the "church of sorrow" slowly became one of joy. The seed that they have planted has grown to maturity in recent years as the church in Yap has begun to furnish its own vocations and assume its own leadership. Because of what they have done, the church of this century will almost certainly be a truly Yapese church. Hezel, Francis X. "The Catholic Church in Micronesia: Historical essays on the Catholic Church in the Caroline-Marshall Islands". ©2003, Micronesian Seminar. All Rights Reserverd. |